Bitcoin is Ponzi populism

Table of contents

Over the past ten years, bitcoin has risen more than 37,000%. How can we explain its success? It’s certainly not because bitcoin has been widely adopted for payments. Instead, bitcoin is fueled by two powerful forces: righteousness and greed. By “righteousness,” I mean non-pecuniary motives for trade including idealism, group identity, and faith. Bitcoin is not just a speculative asset, it’s a social movement, and some people buy bitcoin to express themselves. You can call bitcoin a cult, a political movement, or a revolution in financial technology, but whatever you call it, it’s not only about getting rich.

Righteousness and greed have driven many social movements, for good or for ill. Let’s consider one enduring human phenomenon: warfare. Historically, humans have gone to war not just for duty, honor, and glory, but also for profit. In the Trojan War, for example, the Greeks were motivated partly by moral outrage and partly by the desire to loot Troy. Indeed, the first page of The Iliad mentions pecuniary motives twice.[1] While personal material gain is no longer a prime motive in modern warfare, it remains a secondary motive, as demonstrated by Russian looting in Ukraine.

Idealism and avarice. God and gold. Love and money. Put these two together, and you have a potent combination. From the medieval Crusades to OpenAI, righteousness and greed have driven many human events. As Cecil Rhodes allegedly said, “pure philanthropy is very well in its way but philanthropy plus five percent is a good deal better.” And in the more succinct words of a conquistador in 1568, “we came to serve God and to get rich.”

To understand bitcoin’s success, we can look back to a forgotten political movement: the bimetallism of the 1890s. Both bitcoin and bimetallism are about righteous money, that is, a revolution in monetary affairs motivated by a conception of social justice.

Bimetallism and bitcoin

Shiller (2019) argues that bimetallism was the nineteenth century version of bitcoin. Now, if you’ve never heard of bimetallism, that’s okay. The details of bimetallism are unimportant, just as the details of bitcoin (Merkle trees, hashing, Layer 2) are unimportant. What’s important is that in 1896, bimetallism was hot stuff, and William Jennings Bryan was what we would call today a “bimetallism bro.”

Will bitcoin end up like bimetallism, an unimportant footnote in monetary history? To answer that question, we need to consider the differing roles of righteousness and greed in these two phenomena. But first, let’s consider the ways in which they are similar: spreading narratives.

Shiller argues that economic narratives drive both social movements and financial bubbles, with stories spreading through the population from person to person. He compares the narratives of bimetallism and bitcoin:

Both bimetallism and bitcoin represent radical ideas for the transformation of the monetary standard, with alleged miraculous benefits to the economy … In both cases, an enormous number of people began to regard the innovation as cool, trendy, or cutting-edge.

In the 1890s, the narrative of bimetallism spread across America like a prairie fire. Advocated first by the Populist Party and adopted by the Democratic Party in 1896 after Bryan’s famous “Cross of Gold” speech, bimetallism peaked around 1900.

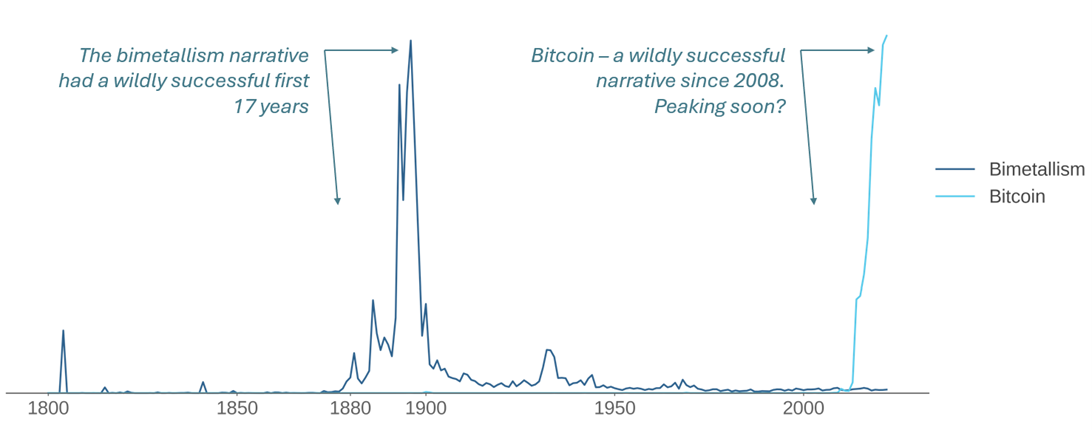

Figure 1, which is my version of Figure 3.2 in Shiller (2019), shows the rise and fall of bimetallism as reflected in mentions in English-language books. The debate over bimetallism was an American obsession in the 1890s. The Wizard of Oz is widely interpreted as a bimetallist parable (in the 1900 book, the ruby slippers are silver). But Bryan was never elected president (despite running three times), bimetallism was never adopted, and the narrative faded from view.

Figure 1 shows that bitcoin, invented in 2008, has so far experienced a trajectory similar to bimetallism. Will the bitcoin narrative soon fade as well? Maybe yes; bitcoin and bimetallism are quite similar on the dimension of righteousness. But maybe no; they’re quite different on the dimension of greed.

Figure 1: Frequency of “bimetallism” and “bitcoin” in published English sources by year, 1800 - 2022

Let’s first consider the role of righteousness. Populists wanted to abandon the gold standard and adopt bimetallism, or “free silver,” a less restrictive monetary system using both gold and silver. They argued that bimetallism would decrease debt burdens and stick it to the fat cats on Wall Street.

Just as mainstream economists today dismiss bitcoin, the mainstream economists of the 1890s dismissed bimetallism and supported the gold standard. The debate was heated. Shiller quotes The New York Times in 1897 as wondering whether bimetallism:

… brings out the natural savagery of its sectaries and makes them delight in the barbarous principles and rough ways of early man?

In modern parallel, Times columnist Paul Krugman wrote a piece on December 28, 2013, titled simply:

Bitcoin is evil

Bimetallism, like bitcoin, aimed to “democratize finance.” The Populist Party of 1892 declared, “the money of the country should be kept as much as possible in the hands of the people.”[2] For a taste of populist outrage against elite condescension, here’s an excerpt from Bryan’s Cross of Gold speech:

We have petitioned, and our petitions have been scorned; we have entreated, and our entreaties have been disregarded; we have begged, and they have mocked when our calamity came. We beg no longer; we entreat no more; we petition no more. We defy them.

… You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns; you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.

Compare with this statement from Coinbase in 2023:[3]

We asked the SEC for reasonable crypto rules for Americans. We got legal threats instead.

Like today’s bitcoin maximalists, bimetallists had extreme views and saw themselves as crusaders. Here’s more from the Cross of Gold speech:

With a zeal approaching the zeal which inspired the crusaders who followed Peter the Hermit, our silver Democrats went forth from victory unto victory, until they are now assembled, not to discuss, not to debate, but to enter up the judgment already rendered by the plain people of this country.

In some ways, bimetallism is the opposite of bitcoin, in that bimetallism was about increasing the money supply to cause inflation, while bitcoin is about a constant money supply to fight inflation. But both share a contempt for prevailing economic orthodoxy and a desire to replace the financial system with something new.

Now let’s consider greed. Bimetallism had a profit motive: cause inflation and benefit indebted farmers at the expense of big-city lenders. And as noted by Friedman (1990), bimetallism was supported by silver miners and silver-producing states.

Bitcoin, however, harnesses greed more effectively than bimetallism. Bimetallism only rewarded its followers if they managed to win political power and change the law. Bitcoin, in contrast, uses a pyramid scheme that rewards early adopters, and attracts additional followers when bitcoin’s price goes up. Perhaps if Bryan had issued his own tradable tokens in 1896, he would’ve become president.

Bitcoin = Beanie Babies + bimetallism

Beanie Babies in the 1990s were a classic bubble involving small stuffed animal toys. The bubble featured a seemingly scarce commodity and an exciting new trading and communications technology, the internet. Early buyers were richly rewarded by price increases, attracting more buyers. Burton and Jacobsen (1999) estimate that the annual returns on Beanie Babies were between 159% and 176% from 1994 to 1999. But the bubble collapsed after 1999, perhaps because Beanie Babies offered no vision of social justice.

Bitcoin combines the Ponzi dynamics of Beanie Babies with the populist appeal of bimetallism. Here are two bitcoin slogans that capture these aspects:

- Righteousness: Fix the money, fix the world. This phrase is a grandiose yet peppy repackaging of the stodgy old idea of sound money.[4]

- Greed: Number go up. “Number go up” (NGU) was originally used to deride bitcoin enthusiasts as greedy simpletons who chased past returns.[5] NGU has since been embraced by the crypto community; bitcoin is said to be “NGU technology” that inevitably rewards purchasers with wealth.

Bitcoin today is a rocket powered by the twin engines of righteousness and greed. There are only two things that can happen to rockets: they either achieve orbital velocity, or they fail and fall out of the sky. Maybe bitcoin will slip the surly bonds of Earth, but my bet is on economic gravity winning in the end.

Endnotes

[1] "Sons of Atreus," he cried, "and all other Achaeans, may the gods who dwell in Olympus grant you to sack the city of Priam, and to reach your homes in safety; but free my daughter, and accept a ransom for her, in reverence to Apollo, son of Jove."

[2] Populist Party Platform, July 1892.

[3] Coinbase blog, March 22, 2023. References to this and other companies should not be interpreted as recommendations to buy or sell specific securities. Acadian and/or the author of this post may hold positions in one or more securities associated with these companies.

[4] It reminds me of “Save the cheerleader, save the world,” the catchphrase of the 2006 superhero drama television series Heroes.

[5] A phenomenon I call The Iron Law of Return-Chasing Flows: Money chases trailing returns.

References

Burton, Benjamin J., and Joyce P. Jacobsen. "Measuring returns on investments in collectibles." Journal of Economic Perspectives 13, no. 4 (1999): 193-212.

Friedman, Milton. "Bimetallism revisited." Journal of Economic Perspectives 4, no. 4 (1990): 85-104.

Shiller, Robert J. Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral and Drive Major Economic Events. Princeton University Press, 2019.

Legal Disclaimer

These materials provided herein may contain material, non-public information within the meaning of the United States Federal Securities Laws with respect to Acadian Asset Management LLC, Acadian Asset Management Inc. and/or their respective subsidiaries and affiliated entities. The recipient of these materials agrees that it will not use any confidential information that may be contained herein to execute or recommend transactions in securities. The recipient further acknowledges that it is aware that United States Federal and State securities laws prohibit any person or entity who has material, non-public information about a publicly-traded company from purchasing or selling securities of such company, or from communicating such information to any other person or entity under circumstances in which it is reasonably foreseeable that such person or entity is likely to sell or purchase such securities.

Acadian provides this material as a general overview of the firm, our processes and our investment capabilities. It has been provided for informational purposes only. It does not constitute or form part of any offer to issue or sell, or any solicitation of any offer to subscribe or to purchase, shares, units or other interests in investments that may be referred to herein and must not be construed as investment or financial product advice. Acadian has not considered any reader's financial situation, objective or needs in providing the relevant information.

The value of investments may fall as well as rise and you may not get back your original investment. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance or returns. Acadian has taken all reasonable care to ensure that the information contained in this material is accurate at the time of its distribution, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of such information.

This material contains privileged and confidential information and is intended only for the recipient/s. Any distribution, reproduction or other use of this presentation by recipients is strictly prohibited. If you are not the intended recipient and this presentation has been sent or passed on to you in error, please contact us immediately. Confidentiality and privilege are not lost by this presentation having been sent or passed on to you in error.

Acadian’s quantitative investment process is supported by extensive proprietary computer code. Acadian’s researchers, software developers, and IT teams follow a structured design, development, testing, change control, and review processes during the development of its systems and the implementation within our investment process. These controls and their effectiveness are subject to regular internal reviews, at least annual independent review by our SOC1 auditor. However, despite these extensive controls it is possible that errors may occur in coding and within the investment process, as is the case with any complex software or data-driven model, and no guarantee or warranty can be provided that any quantitative investment model is completely free of errors. Any such errors could have a negative impact on investment results. We have in place control systems and processes which are intended to identify in a timely manner any such errors which would have a material impact on the investment process.

Acadian Asset Management LLC has wholly owned affiliates located in London, Singapore, and Sydney. Pursuant to the terms of service level agreements with each affiliate, employees of Acadian Asset Management LLC may provide certain services on behalf of each affiliate and employees of each affiliate may provide certain administrative services, including marketing and client service, on behalf of Acadian Asset Management LLC.

Acadian Asset Management LLC is registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration of an investment adviser does not imply any level of skill or training.

Acadian Asset Management (Singapore) Pte Ltd, (Registration Number: 199902125D) is licensed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited (ABN 41 114 200 127) is the holder of Australian financial services license number 291872 ("AFSL"). It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Under the terms of its AFSL, Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited is limited to providing the financial services under its license to wholesale clients only. This marketing material is not to be provided to retail clients.

Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority ('the FCA') and is a limited liability company incorporated in England and Wales with company number 05644066. Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited will only make this material available to Professional Clients and Eligible Counterparties as defined by the FCA under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive, or to Qualified Investors in Switzerland as defined in the Collective Investment Schemes Act, as applicable.