Lessons from Labubu

Table of contents

Labubu mania is sweeping across the globe. If you don’t recognize the name, perhaps you’ve seen one online: a small plush monster doll that is both a toy and a fashion statement. On TikTok and Instagram, you can see Labubus sported by celebrities including Dua Lipa, Rihanna, and Tom Brady. When Labubus go on sale, retail outlets are mobbed by unruly customers. Demand greatly exceeds supply, and there’s a brisk secondary market where Labubus sell at a hefty premium to the retail price.

How should we interpret these events? Is it Beanie Babies all over again? Is the demand for Labubus irrational? Does Labubu mania tell us something about this moment in financial history?

Briefly, my take is:

- No, Labubus are not Beanie Babies all over again, at least not yet.

- No, I don’t see the desire to buy Labubus as irrational.

- Yes, Labubu mania is representative of today’s stock market: risk-loving, meme-driven, and prone to wild swings in sentiment.

The Labubu phenomenon

Like many things in modern pop culture, good and bad, Labubu mania originated in Korea. While various versions of Labubus have been manufactured since 2015, the global craze only took off in April 2024 when Lisa, a K-pop star, started posting images of her various Labubus.

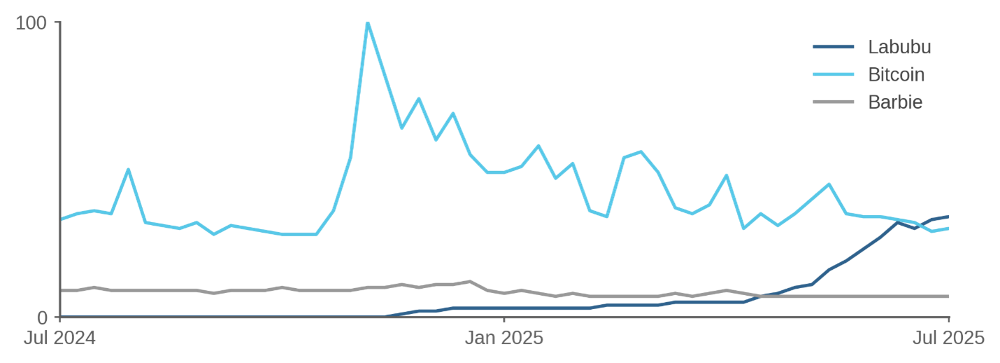

Labubu mania spread first in East Asia, including China and Thailand as well as Korea, then grew worldwide. As can be seen in the dark blue line in Figure 1, Google search activity for Labubu accelerated in early 2025, exceeding first Barbie (the gray line) and more recently bitcoin (the light blue line). In the U.K., excitement over Labubus was so intense that fights broke out at retail stores, and the company that manufactures Labubus decided in May 2024 to halt in-store sales to “prevent any potential safety issues."

Part of the appeal of Labubus is that they are sold in “blind boxes,” that is, you don’t find out which doll you have purchased until you open the box. The box may contain a rare and valuable collectible or it may contain a common doll that you already have. This retailing gimmick, used for decades in baseball cards and in mystery prizes, is supercharged in a world of social media where you can post your dramatic unboxing on TikTok.

Figure 1: Worldwide Google Search Activity for Labubu versus Barbie and Bitcoin

Labubu Labubble?

While I would describe the Labubu phenomenon as a mania or a craze, I would not describe it as a bubble, which I define as a self-sustaining rise in prices over time resulting in the speculative trading of an obviously overvalued asset. Speculative bubbles are a subset of contagious social behavior, a large category of diverse phenomena including witch-hunting in Europe around 1500, hula hoops in the 1950s, and viral videos today. These contagious behaviors mostly do not involve speculative trading. Shiller (2012) discriminates between “social epidemics” versus “speculative bubbles,” while Hirshleifer (2020) calls them “action booms” versus “price bubbles.”

While there is reselling of Labubus, and I suppose some buyers are engaged in speculative trading, I don’t see evidence that most buyers are planning to resell their Labubus or are especially interested in the rising prices of Labubus on the secondary market. So I see Labubus as an example of contagious social behavior leading to a wave of product buying, but not as a speculative bubble like Beanie Babies. In the case of Beanie Babies, as described in Burton and Jacobsen (1999), expectations about future price appreciation were a key driver of purchasing.

There have been many instances of consumer manias involving small dolls. These include Kewpie Dolls in the early 20th century, Cabbage Patch Kids in the 1980s, and Tickle Me Elmo in the 1990s. Many of these manias involve frenzies of buying, scarcity, and reselling on the secondary market, but as far as I know, only in the case of Beanie Babies did the initial mania transform into a speculative bubble where purchasers bought the item primarily for pecuniary motives. Only with Beanie Babies did the whimsical dolls bought by “children with allowances” morph into a speculative asset bought by “creepy, belligerent men.”[1]

Right now, Labubus are more Tickle Me Elmo than Beanie Babies. But if you see charlatans on TikTok recommending a 60/40 portfolio that is 60% crypto, 40% Labubus, then you will know we have reached Beanie Baby territory.

Putting aside the bubble question, is it irrational if I buy a Labubu when I see my favorite celebrity buying? I don’t think so. Fads and fashions are not necessarily irrational. It is not irrational for me to enjoy listening to “A Bar Song (Tipsy)” by Shaboozey, nor is it irrational for my enjoyment to be enhanced by discussing the song with fellow fans. While Hirshleifer (2020) discusses “visibility bias” that may cause people to overconsume Labubus that they see on TikTok, it is not necessary to have a cognitive bias in order to have social epidemics of shared consumption.

The plush troll in the mirror

I think there are several elements of the Labubu phenomenon that make it emblematic of today’s financial markets:

- Risk is viewed as good. Traditionally, financial economists have seen risk as a bad thing and, thus, have predicted that risky assets should have lower valuations. But today in many financial markets, risk taking is valorized and risky assets seem to be overvalued. The blind-box mechanism adds a spice of risk to the consumer experience and is part of today’s gamblified, gamified culture.

- Scarcity drives the narrative. The makers of Labubus have managed to whip up consumer interest by making them scarce and therefore valuable. Like Beanie Babies and Tickle Me Elmo before them, part of the mania involves the exciting consumer quest to actually purchase the product. Every con artist knows that you want to get the mark invested in the con by making them come to you. Similarly, the narrative about crypto is that it is scarce and therefore valuable. In both cases, the scarcity is artificial but the resulting behavior is real.

- Social media and celebrities supercharge the virality. Social media serves as the interface between the top-down phenomenon of celebrity behavior and the bottom-up phenomenon of consumer behavior. That is, I see my favorite celebrity on TikTok with a Labubu, and I want to be part of that shared experience. While decades ago this process involved seeing a celebrity on TV, today social media makes the shared experience more immediate, more intimate, and more interactive. While Labubus are a relatively benign contagion, social media also spreads more harmful financial content.

The Labubu manufacturer describes its product as follows:

Despite a mischievous look, LABUBU is kind-hearted and always wants to help, but often accidentally achieves the opposite.

To me, that sounds a lot like the typical retail investor.

Endnotes

[1] “The Beanie Baby Boom And Bust – What Happened?,” WBUR, March 2, 2015.

References

Burton, Benjamin J., and Joyce P. Jacobsen. "Measuring returns on investments in collectibles." Journal of Economic Perspectives 13, no. 4 (1999): 193-212.

Hirshleifer, David. "Presidential address: Social transmission bias in economics and finance." The Journal of Finance 75, no. 4 (2020): 1779-1831.

Shiller, Robert. “Bubbles without markets,” Project Syndicate, July 23, 2012.

Legal Disclaimer

These materials provided herein may contain material, non-public information within the meaning of the United States Federal Securities Laws with respect to Acadian Asset Management LLC, Acadian Asset Management Inc. and/or their respective subsidiaries and affiliated entities. The recipient of these materials agrees that it will not use any confidential information that may be contained herein to execute or recommend transactions in securities. The recipient further acknowledges that it is aware that United States Federal and State securities laws prohibit any person or entity who has material, non-public information about a publicly-traded company from purchasing or selling securities of such company, or from communicating such information to any other person or entity under circumstances in which it is reasonably foreseeable that such person or entity is likely to sell or purchase such securities.

Acadian provides this material as a general overview of the firm, our processes and our investment capabilities. It has been provided for informational purposes only. It does not constitute or form part of any offer to issue or sell, or any solicitation of any offer to subscribe or to purchase, shares, units or other interests in investments that may be referred to herein and must not be construed as investment or financial product advice. Acadian has not considered any reader's financial situation, objective or needs in providing the relevant information.

The value of investments may fall as well as rise and you may not get back your original investment. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance or returns. Acadian has taken all reasonable care to ensure that the information contained in this material is accurate at the time of its distribution, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of such information.

This material contains privileged and confidential information and is intended only for the recipient/s. Any distribution, reproduction or other use of this presentation by recipients is strictly prohibited. If you are not the intended recipient and this presentation has been sent or passed on to you in error, please contact us immediately. Confidentiality and privilege are not lost by this presentation having been sent or passed on to you in error.

Acadian’s quantitative investment process is supported by extensive proprietary computer code. Acadian’s researchers, software developers, and IT teams follow a structured design, development, testing, change control, and review processes during the development of its systems and the implementation within our investment process. These controls and their effectiveness are subject to regular internal reviews, at least annual independent review by our SOC1 auditor. However, despite these extensive controls it is possible that errors may occur in coding and within the investment process, as is the case with any complex software or data-driven model, and no guarantee or warranty can be provided that any quantitative investment model is completely free of errors. Any such errors could have a negative impact on investment results. We have in place control systems and processes which are intended to identify in a timely manner any such errors which would have a material impact on the investment process.

Acadian Asset Management LLC has wholly owned affiliates located in London, Singapore, and Sydney. Pursuant to the terms of service level agreements with each affiliate, employees of Acadian Asset Management LLC may provide certain services on behalf of each affiliate and employees of each affiliate may provide certain administrative services, including marketing and client service, on behalf of Acadian Asset Management LLC.

Acadian Asset Management LLC is registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration of an investment adviser does not imply any level of skill or training.

Acadian Asset Management (Singapore) Pte Ltd, (Registration Number: 199902125D) is licensed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited (ABN 41 114 200 127) is the holder of Australian financial services license number 291872 ("AFSL"). It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Under the terms of its AFSL, Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited is limited to providing the financial services under its license to wholesale clients only. This marketing material is not to be provided to retail clients.

Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority ('the FCA') and is a limited liability company incorporated in England and Wales with company number 05644066. Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited will only make this material available to Professional Clients and Eligible Counterparties as defined by the FCA under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive, or to Qualified Investors in Switzerland as defined in the Collective Investment Schemes Act, as applicable.