AI and the stock market: What’s the worst-case scenario?

I’ve previously argued that the stock market is not in an AI bubble. But that doesn’t mean that everything is sunshine and rainbows. I view today’s stock market as having both unusually large upside and unusually large downside. In this piece, I want to sketch out the worst-case scenario for global equities.

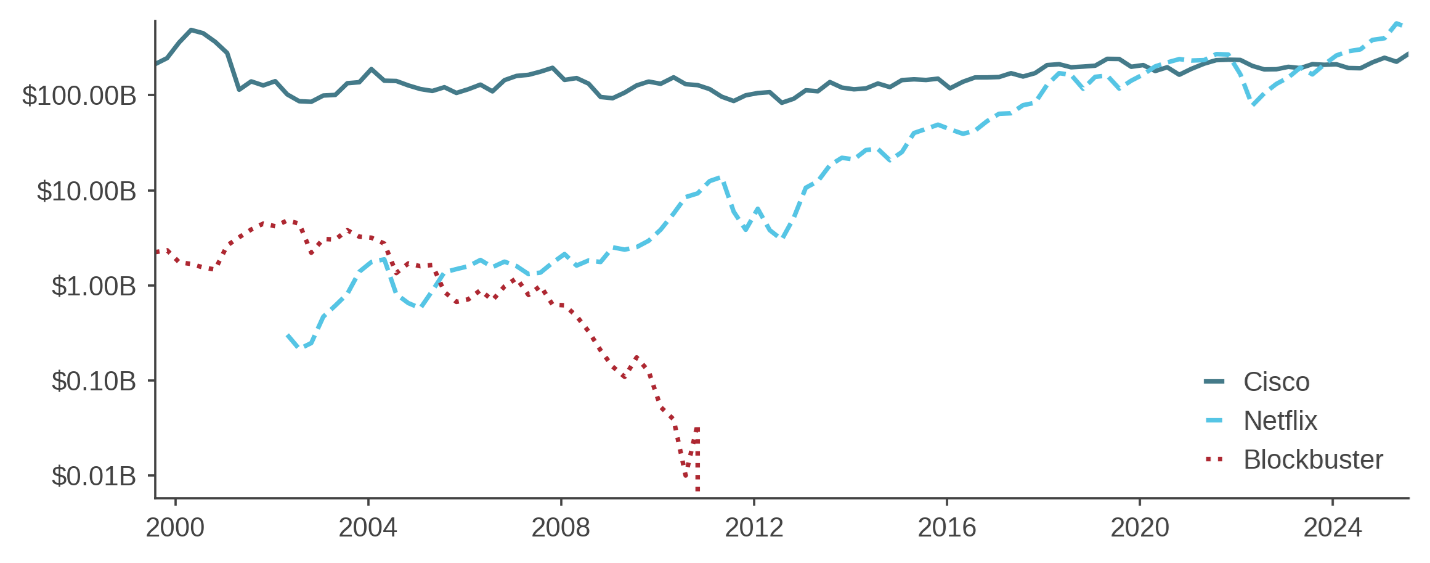

Consider the U.S. stock market in 1999. Figure 1 shows the market capitalization of three firms: Cisco, Blockbuster Video, and Netflix.[1] Much of the recent debate revolves around whether today’s market resembles Cisco in 1999. But that’s hardly the worst-case scenario. The worst-case scenario is that today’s market resembles Blockbuster. Innovation always has winners and losers, and if most currently public firms turn out to be AI losers, then the market is heading for a fall.

In 1999, Cisco was correctly perceived as a technology winner, and it subsequently experienced enormous growth in revenue and profits. This growth was, however, insufficient to justify Cisco’s valuation, and thus Cisco’s price subsequently fell as the tech-stock bubble deflated. But the main story in Figure 1 is that Cisco, while overvalued in 1999, was a technology winner.

In contrast, Blockbuster suffered greatly from the rise of the internet. Like the mighty herds of buffalo that once roamed America, Blockbuster went from being ubiquitous (with more than 9,000 locations in 2004) to nearly extinct (today, a single video rental location remains in Bend, Oregon).

Netflix prospered at the expense of Blockbuster. It was a private company in 1999 and did not IPO until 2002. Thus, if you held the U.S. stock market, you did not benefit from Netflix’s initial success from 1999 to 2002, for the simple reason that Netflix was not publicly traded in 1999.

So, why did stock prices go up in the 1990s? Market participants perceived that the winners would greatly benefit from the internet and the losers would not be greatly hurt. In retrospect, it appears that the market overestimated technology’s benefit to Cisco and underestimated technology’s harm to Blockbuster, neglecting to realize that many of the benefits would flow to private firms like Netflix. Similarly, I expect many of the big AI winners will be companies that currently do not exist.

Figure 1: Market capitalizations of Cisco, Blockbuster, and Netflix

Log scale, billions of USD

Currently, market participants seem to think the U.S. stock market is dominated by winners. The worst-case scenario is that investors change their minds and decide that existing public firms are like Blockbuster (doomed to extinction). That’s not what happened in the 1990s, but it is a possibility going forward.

AI is a wonderful new technology that will enhance economic productivity. It may seem strange to think it might hurt the stock market, because historically new technology has often produced stock market booms, as with railroads, automobiles, and the internet. But stock market booms are not the only possible outcome of innovation. The impact depends on whether the stock market contains more technology winners or more technology losers.

Consider the 1920s stock market boom. It involved exciting new products such as the automobile and fast-growing companies such as General Motors. But the 1920s boom had losers as well as winners. Among the losers were firms and individuals involved in what was then a central part of the economy: horses.

Around 1920, the U.S. horse population reached its peak with approximately one horse for every four humans. The rise of the internal combustion engine was a devastating blow to the equine industrial complex. Some firms successfully made the transition to the post-horse economy, with blacksmiths becoming auto mechanics and wagonmakers becoming automakers (for example, NYSE-listed Studebaker). But mostly, the horse economy simply collapsed in the 1920s.

America experienced an agricultural depression and waves of bankruptcies in the 1920s, partly due to the demise of horses. The shrinking horse population may have even played a role in the overall economic collapse of the 1930s, with the Commerce Department concluding in 1933 that it “is one of the main contributing factors of the present economic situation … has affected the entire country.”[2]

As it turned out, almost all horse-related enterprises were privately held. The stock market boomed in the 1920s partly because auto-related firms were public but horse-related firms were not. Imagine an alternative universe where, in 1920, the stock market consisted only of horse-related firms, with General Motors and U.S. Steel being private but the hypothetical firms General Horses and U.S. Hay being public. In that universe, stock prices would fall in the 1920s.

The process by which horses and video stores are replaced by new technology from new firms is called “creative destruction.” According to Schumpeter (1942), “Creative Destruction is the essential fact about capitalism.” Many economic models predict that new technology should cause stock prices to fall, not rise, as Schumpeterian creative destruction impacts existing firms (see Jovanovic and Rousseau (2005) for a literature review). Hobijn and Jovanovic (2001) claim that this dynamic caused U.S. stock prices to fall after the introduction of the microprocessor in the early 1970s. I’m not sure their story is a plausible explanation for the horrific bear market of the 1970s, but it’s definitely a plausible scenario for the impact of AI going forward. And it doesn’t matter whether this obsolescence narrative is true; it matters whether market participants believe the narrative is true.

AI will likely unleash a wave of economic growth. But the benefits of this growth may not flow to today’s shareholders. Ritter (2005) studied different countries and found that, contrary to conventional wisdom, high future economic growth does not generally benefit current shareholders:

If an economy grows because personal savings are invested in new firms … the gains on this capital investment do not accrue to existing shareholders.

As always, The Stock Market Is Not The Economy or simply TSMINTE.

I’m an AI optimist. I’m hoping AI will generate scientific breakthroughs that make everybody richer, healthier, and happier. But these breakthroughs would not necessarily be great for existing public companies. Goldman Sachs has a list of equities most at risk from AI, including firms in IT services, payroll services, and business process outsourcing. Share prices of these firms have fallen in half since 2021. But what if that’s just the beginning? What if AI cures all diseases, decimating the health care sector? What if AI invents cold fusion, making oil firms worthless? Maybe all existing stocks belong on the list of at-risk firms.

To quote Donald Rumsfeld, you go to war with the army you have, not the army you want. Similarly, you go to the AI revolution with the stock market you have, not the stock market you want. As Blockbuster shareholders discovered, creative destruction is no fun when it’s your wealth that’s getting creatively destroyed.

Endnotes

[1] References to this and other companies should not be interpreted as recommendations to buy or sell specific securities. Acadian and/or the author of this post may hold positions in one or more securities associated with these companies.

[2] “1930 Census of Agriculture: The Farm Horse,” United States Department of Commerce, 1933.

References

Hobijn, Bart, and Boyan Jovanovic. "The information-technology revolution and the stock market: Evidence." American Economic Review 91, no. 5 (2001): 1203-1220.

Jovanovic, Boyan, and Peter L. Rousseau. "General purpose technologies." In Handbook of Economic Growth, vol. 1, pp. 1181-1224. Elsevier, 2005.

Ritter, Jay R. "Economic growth and equity returns." Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 13, no. 5 (2005): 489-503.

Schumpeter, Joseph A. Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. 1942.

Don't miss the next Owenomics

Subscribe to receive new articles as they are published from Senior Portfolio Manager and Research, Owen Lamont

Legal Disclaimer

These materials provided herein may contain material, non-public information within the meaning of the United States Federal Securities Laws with respect to Acadian Asset Management LLC, Acadian Asset Management Inc. and/or their respective subsidiaries and affiliated entities. The recipient of these materials agrees that it will not use any confidential information that may be contained herein to execute or recommend transactions in securities. The recipient further acknowledges that it is aware that United States Federal and State securities laws prohibit any person or entity who has material, non-public information about a publicly-traded company from purchasing or selling securities of such company, or from communicating such information to any other person or entity under circumstances in which it is reasonably foreseeable that such person or entity is likely to sell or purchase such securities.

Acadian provides this material as a general overview of the firm, our processes and our investment capabilities. It has been provided for informational purposes only. It does not constitute or form part of any offer to issue or sell, or any solicitation of any offer to subscribe or to purchase, shares, units or other interests in investments that may be referred to herein and must not be construed as investment or financial product advice. Acadian has not considered any reader's financial situation, objective or needs in providing the relevant information.

The value of investments may fall as well as rise and you may not get back your original investment. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance or returns. Acadian has taken all reasonable care to ensure that the information contained in this material is accurate at the time of its distribution, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of such information.

This material contains privileged and confidential information and is intended only for the recipient/s. Any distribution, reproduction or other use of this presentation by recipients is strictly prohibited. If you are not the intended recipient and this presentation has been sent or passed on to you in error, please contact us immediately. Confidentiality and privilege are not lost by this presentation having been sent or passed on to you in error.

Acadian’s quantitative investment process is supported by extensive proprietary computer code. Acadian’s researchers, software developers, and IT teams follow a structured design, development, testing, change control, and review processes during the development of its systems and the implementation within our investment process. These controls and their effectiveness are subject to regular internal reviews, at least annual independent review by our SOC1 auditor. However, despite these extensive controls it is possible that errors may occur in coding and within the investment process, as is the case with any complex software or data-driven model, and no guarantee or warranty can be provided that any quantitative investment model is completely free of errors. Any such errors could have a negative impact on investment results. We have in place control systems and processes which are intended to identify in a timely manner any such errors which would have a material impact on the investment process.

Acadian Asset Management LLC has wholly owned affiliates located in London, Singapore, and Sydney. Pursuant to the terms of service level agreements with each affiliate, employees of Acadian Asset Management LLC may provide certain services on behalf of each affiliate and employees of each affiliate may provide certain administrative services, including marketing and client service, on behalf of Acadian Asset Management LLC.

Acadian Asset Management LLC is registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration of an investment adviser does not imply any level of skill or training.

Acadian Asset Management (Singapore) Pte Ltd, (Registration Number: 199902125D) is licensed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited (ABN 41 114 200 127) is the holder of Australian financial services license number 291872 ("AFSL"). It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Under the terms of its AFSL, Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited is limited to providing the financial services under its license to wholesale clients only. This marketing material is not to be provided to retail clients.

Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority ('the FCA') and is a limited liability company incorporated in England and Wales with company number 05644066. Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited will only make this material available to Professional Clients and Eligible Counterparties as defined by the FCA under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive, or to Qualified Investors in Switzerland as defined in the Collective Investment Schemes Act, as applicable.