Dumb money triumphant

Is the U.S. stock market in a bubble? I doubt we’re there yet, but one sign of speculative froth is the recent success of retail investors. On average, retail investors exhibit anti-skill in their stock selection decisions, meaning that their holdings underperform the market. So when retail investors are winning, that tells you that market conditions are unusual.

It is fair to describe retail investors as “dumb money.” While some find this phrase offensive, I think it’s accurate. The word “dumb” is meant to describe their behavior, as opposed to their innate intelligence. Retail investors include highly intelligent and educated professionals, such as doctors and dentists. But they have a well-documented habit of making investment decisions that result in significant destruction of their own wealth, in other words, dumb behavior. Similarly, if finance professors ever try to perform surgery on themselves, it would be fair to call them “dumb surgery.”

When market prices get dumb, the dumb money gets rich. The initial success of the first wave of dumb money motivates a second wave of dumb money, which pushes up prices further. This feedback loop, Shiller’s “naturally occurring Ponzi scheme,” creates market bubbles. Lefèvre (1923) writes:

The big money in booms is always made first by the public – on paper. And it remains on paper.

According to this view, retail investors win in the initial stage of the bubble, but eventually lose when the bubble deflates. Take, for example, the tech-stock bubble. It is clear that retail investors, partly acting indirectly via mutual funds as shown in Frazzini and Lamont (2008), bought tech stocks such as Cisco in the late 1990s.[1]

Here’s one story about the tech-stock bubble. Retail buying drove up the price of tech stocks such as Cisco, attracting yet more retail inflows. By the end of 1999, Cisco was one of the best-performing stocks, and retail investors, as a group, had outperformed. Call this retail outperformance “dumb alpha.” As of 1999, not only were tech stocks overpriced compared to other stocks, but the whole market was overpriced as its composition tilted toward tech. Thus, by late 1999, trailing positive dumb alpha coincided with an overpriced market.

This retail success couldn’t last, because prices eventually return to fundamental value. Thus, the positive dumb alpha of the late 1990s turned into the sharply negative dumb alpha of the early 2000s as the bubble deflated. Over long periods, retail investors lose, so dumb alpha is negative on average. However, during speculative episodes such as 1999 and 2021, dumb alpha can be positive.

Another example of positive dumb alpha comes from the initial stages of the South Sea Bubble of 1720. Here’s Edward Ward in his poem “A South-Sea Ballad, or, Merry Remarks upon Exchange-Alley Bubbles:”

Few men who follow reason’s rules

Grow fat with South Sea diet;

Young rattles and unthinking fools

Are those who flourish by it.

As of today, unthinking fools are once again flourishing while those who follow reason’s rules are not. We see ample evidence of positive dumb alpha in the U.S. stock market, as retail investors have outperformed the broad market over the past year.

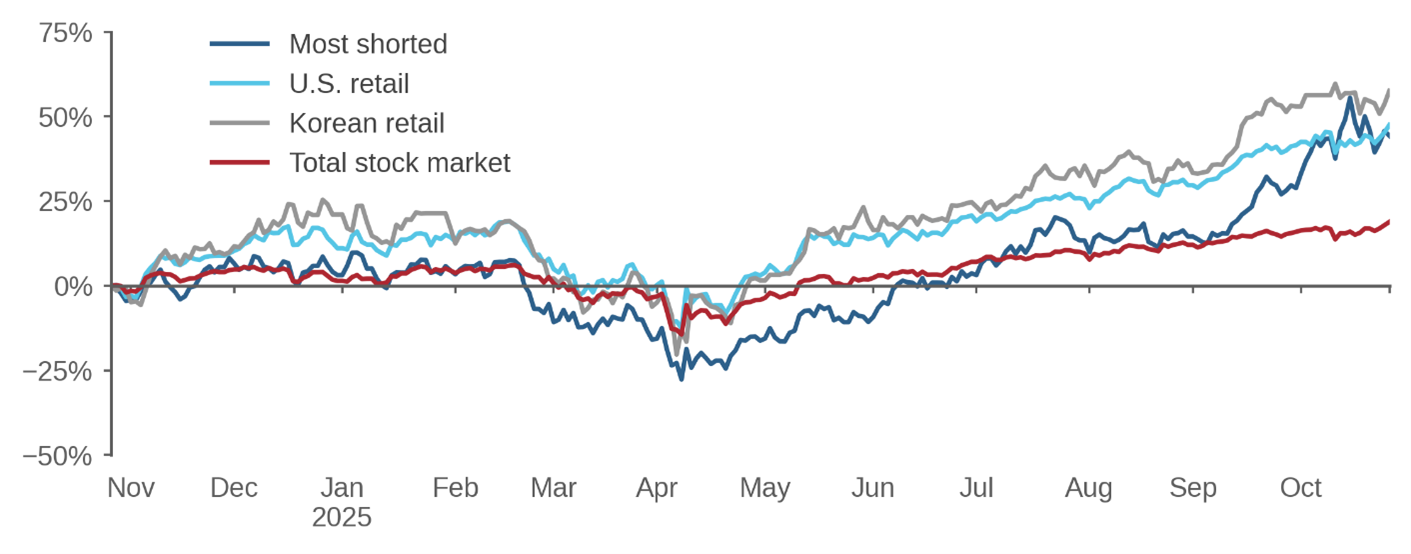

Figure 1 shows cumulative returns on two ETFs reflecting retail investor holdings of U.S. stocks, one for U.S. investors and one for Korean investors. For U.S. retail investors, the SoFi Social 50 ETF consists of the top 50 holdings of clients of SoFi, a brokerage primarily serving U.S. customers. For Korean retail investors, the Samsung KODEX Investor’s Choice ETF consists of the top 25 U.S. common stocks held by Korean retail investors, as reported by the Korea Securities Depositary. In the past year, both of these ETFs have greatly outperformed, with total returns more than double those of the broad U.S. market, as measured by the Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF.

Figure 1: Smart money vs. dumb money

Since the dumb money is winning, you know that the smart money must be losing. Short sellers have been among the smartest money, historically. Typically, the stocks that short sellers sell are the same stocks that retail investors buy, as shown by McLean, Pontiff, and Reilly (2025). On average, short sellers win, since the stocks they short subsequently underperform. But lately, short sellers have been losing. Figure 1 shows the performance of the Goldman Sachs basket of most-shorted stocks. When these stocks go up, the smart money is hurting. The smart money has endured quite a bit of pain, especially in the past few months.

Dumb money winning, smart money losing—that’s a market heading down the road to crazy high prices for some popular stocks and possibly crazy high prices for the whole market. We saw a similar configuration of performance in 2021, which was followed by a decline in the whole market in 2022, but an especially severe decline in retail favorites, as the dumb alpha turned sharply negative.

Historically, stock market bubbles (and, more recently, crypto bubbles) have been fueled by stories about ordinary people becoming fabulously wealthy through their investments. Let me focus on just one group: waiters. When waiters are getting rich, maybe that’s the sign of a market top.

Consider this passage from The New York Times Magazine, March 24, 1929:

THE MAGNET OF DANCING STOCK PRICES; Playing the Market Is Now a Pastime And the Amateur Has His Day

The old-fashioned Wall Street theory that a bull market does not exist unless it is being played by bootblacks, household servants, clerks and others who ordinarily have but small amounts of surplus funds, has again been borne out. They are in the market by the hundreds, and some of them have rolled up luscious profits on their ten, twenty and fifty shares of stock. Two veteran waiters, who have given many years of their lives to service in the Bankers Club, have recently retired on profits accumulated in the market on advice given to them freely by men to whom they were accustomed to serve luncheon. One of them purchased a modest restaurant on Staten Island, paying for it in cash with his market profits. The other bought a farm on Long Island and is making plans for a fine little garden this Spring.

… It is quite true that the people who know least about the stock market have made the most money out of it in the last few months. Fools who rushed in where wise men feared to tread ran up high gains.

Now fast forward to the tech-stock bubble and take a look at Forbes from January 25, 1999:

Amateur hour on Wall Street

… a 25-year-old former waiter from Queens, N.Y., has a Pro-Star 300-megahertz Pentium laptop patched into E-Trade via America Online. With those tools, trading in and out of stocks like Navarre and Netscape, he turned $1,100 into $100,000 in two months. "Before, I was investing for the long term and I found out that it was not smart. Now my goal is a 1,000% return by 2000," he says.

… Each day a 5-million-strong mob of on-line investors is proving that when it comes to stock picking, might makes right. In their world, everything you have learned about rational pricing -- earnings or book values or even revenues -- is meaningless. Don't worry about the long haul.

Trade for the moment. Make a killing. Hey, everyone else in the chat group seems to be doing so.

Finally, we turn to the present day and find this piece in The Wall Street Journal, October 10, 2025:

More Working-Class Americans Than Ever Are Investing in the Stock Market

… he started putting almost every dollar of his paycheck from working as a server at the Cheesecake Factory into his investments. He followed influencers on X and YouTube who post frequently about their stock picks.

In 2023, he purchased hundreds of shares of data-analytics company Palantir. The next year, a wave of enthusiasm among individual investors like Cheney propelled the stock’s meteoric rise. The share price is up roughly 900% in the past two years.

… managing his seven-figure investment account is his primary passion.

“I feel like there’s been a shift,” he said. “Before retail was scoffed at. Now we’re a huge voice in how markets work.”

The similarities between 1929, 1999, and today are uncanny. Of course, it’s always possible to find winners in the stock market, just as it’s possible to find winners at the casino, so these anecdotes are only suggestive. That’s why the aggregate evidence shown in Figure 1 is helpful.

The two waiters mentioned in the 1929 article got out at the right time, converting their stock market winnings into other assets (a restaurant and a farm). But that’s not what retail investors typically do. Here’s Lefèvre again:

In a bull market and particularly in booms the public at first makes money which it later loses simply by overstaying the bull market.

So, is it time to get out of the stock market? I don’t know, but maybe you should head over to your local Cheesecake Factory and ask around.

Endnotes

[1] References to this and other companies should not be interpreted as recommendations to buy or sell specific securities. Acadian and/or the author of this post may hold positions in one or more securities associated with these companies.

References

Frazzini, Andrea, and Owen A. Lamont. "Dumb money: Mutual fund flows and the cross-section of stock returns." Journal of Financial Economics 88, no. 2 (2008): 299-322.

Lefèvre, Edwin. Reminiscences of a Stock Operator, New York. 1923.

McLean, R. David, Jeffrey Pontiff, and Christopher Reilly. "Taking sides on return predictability." Journal of Financial Economics 173 (2025): 104158.

Legal Disclaimer

These materials provided herein may contain material, non-public information within the meaning of the United States Federal Securities Laws with respect to Acadian Asset Management LLC, Acadian Asset Management Inc. and/or their respective subsidiaries and affiliated entities. The recipient of these materials agrees that it will not use any confidential information that may be contained herein to execute or recommend transactions in securities. The recipient further acknowledges that it is aware that United States Federal and State securities laws prohibit any person or entity who has material, non-public information about a publicly-traded company from purchasing or selling securities of such company, or from communicating such information to any other person or entity under circumstances in which it is reasonably foreseeable that such person or entity is likely to sell or purchase such securities.

Acadian provides this material as a general overview of the firm, our processes and our investment capabilities. It has been provided for informational purposes only. It does not constitute or form part of any offer to issue or sell, or any solicitation of any offer to subscribe or to purchase, shares, units or other interests in investments that may be referred to herein and must not be construed as investment or financial product advice. Acadian has not considered any reader's financial situation, objective or needs in providing the relevant information.

The value of investments may fall as well as rise and you may not get back your original investment. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance or returns. Acadian has taken all reasonable care to ensure that the information contained in this material is accurate at the time of its distribution, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of such information.

This material contains privileged and confidential information and is intended only for the recipient/s. Any distribution, reproduction or other use of this presentation by recipients is strictly prohibited. If you are not the intended recipient and this presentation has been sent or passed on to you in error, please contact us immediately. Confidentiality and privilege are not lost by this presentation having been sent or passed on to you in error.

Acadian’s quantitative investment process is supported by extensive proprietary computer code. Acadian’s researchers, software developers, and IT teams follow a structured design, development, testing, change control, and review processes during the development of its systems and the implementation within our investment process. These controls and their effectiveness are subject to regular internal reviews, at least annual independent review by our SOC1 auditor. However, despite these extensive controls it is possible that errors may occur in coding and within the investment process, as is the case with any complex software or data-driven model, and no guarantee or warranty can be provided that any quantitative investment model is completely free of errors. Any such errors could have a negative impact on investment results. We have in place control systems and processes which are intended to identify in a timely manner any such errors which would have a material impact on the investment process.

Acadian Asset Management LLC has wholly owned affiliates located in London, Singapore, and Sydney. Pursuant to the terms of service level agreements with each affiliate, employees of Acadian Asset Management LLC may provide certain services on behalf of each affiliate and employees of each affiliate may provide certain administrative services, including marketing and client service, on behalf of Acadian Asset Management LLC.

Acadian Asset Management LLC is registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration of an investment adviser does not imply any level of skill or training.

Acadian Asset Management (Singapore) Pte Ltd, (Registration Number: 199902125D) is licensed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited (ABN 41 114 200 127) is the holder of Australian financial services license number 291872 ("AFSL"). It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Under the terms of its AFSL, Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited is limited to providing the financial services under its license to wholesale clients only. This marketing material is not to be provided to retail clients.

Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority ('the FCA') and is a limited liability company incorporated in England and Wales with company number 05644066. Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited will only make this material available to Professional Clients and Eligible Counterparties as defined by the FCA under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive, or to Qualified Investors in Switzerland as defined in the Collective Investment Schemes Act, as applicable.