The Illusion of Compound Returns

Table of contents

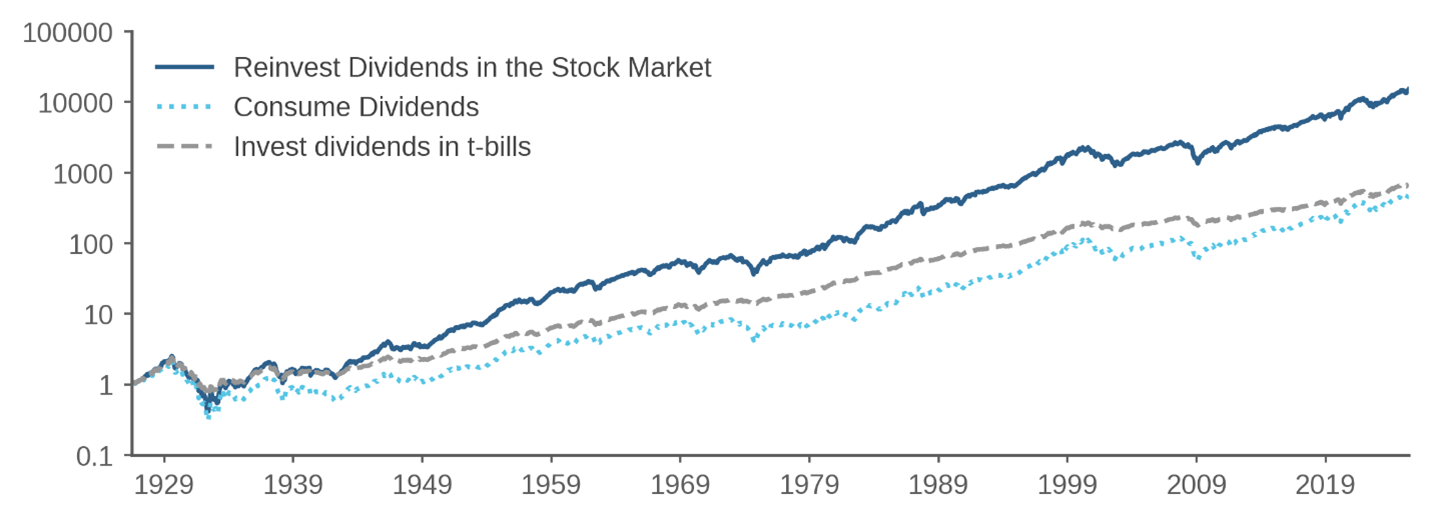

We’ve all seen the graph. If you put $1 into the stock market in 1926, and reinvested the dividends, you’d have more than $10,000 today. The solid line in Figure 1 shows the familiar pattern, reflecting the incredible power of compound returns. Fantastic! Wouldn’t it be great if everyone just pursued this buy-and-hold strategy?

Figure 1: Total returns on the CRSP VW aggregate stock market

Now, there are several reasons that Figure 1 might be misleading going forward. First, it is based on total nominal returns, and thus does not reflect inflation, expenses, and taxes. Second, perhaps the next century of stock returns will be less fantastic than the previous century, with lower returns.

But I’d like to discuss a more basic reason that Figure 1 is potentially misleading: it uses compounded returns and reinvested dividends. I’m all in favor of compounding and reinvesting dividends, but unfortunately, you can’t always do it. Compounding is a mighty force, but there is a force mightier still: capacity.

While holding stocks and reinvesting dividends is a great strategy for any one individual, “everyone reinvests dividends forever” violates the requirement of market clearing. Market clearing means that total dollar value of buys must equal total dollar value of sells. If no one wants to sell when you want to buy, you’ve just hit a capacity constraint, and the market has failed to clear.

“Everyone reinvests dividends forever” violates market clearing in two ways. First, everyone can’t reinvest dividends simultaneously. We can’t all reinvest our dividends by buying shares, because someone somewhere needs to sell us those shares. Second, even if we focus on just one individual, I can’t reinvest dividends forever, because eventually I will run out of sellers. It is not possible for me to invest $1 in the stock market and reinvest dividends forever, because eventually I will end up holding the entire stock market.

Now, in theory, we could increase the capacity of the stock market by having firms issue more equity. If firms continually increased the number of shares available to buy, then it would be possible for everyone (defined as “everyone except firms”) to reinvest dividends forever. In reality, however, U.S. corporations have repurchased equity on average, and so in this sense the capacity of the stock market has actually fallen over time, not risen.

The problem is that buy-and-hold is not actually buy-and-hold. Instead, buy-and-hold with reinvested dividends is actually buy-and-buy. You need to reinvest dividends as they are paid, and that requires you to buy more shares periodically. So reinvesting dividends is really a dynamic trading strategy and not a passive holding strategy (I’ll discuss the elusive nature of “passively holding the market” below.)

When you are able to compound, it is a wonderful thing. As Benjamin Franklin said:

Money makes money. And the money that money makes, makes money.

Unfortunately, money doesn’t make money in every conceivable situation; money requires capacity to make money.

Consider the following statement: “bunnies make bunnies.” The mathematics of rabbit reproduction have been formally modeled starting with Fibonacci in the thirteenth century. If we start with two rabbits, and these rabbits make more rabbits, the math says that in a surprisingly short time the entire surface of the earth will be covered with a layer of rabbits three feet deep.

We all recognize that this math is absurd because it ignores the capacity of the earth to support rabbits. Similarly, the statement that “everyone should hold the market and reinvest dividends forever” ignores the capacity of the stock market to absorb dollars.

Now, as a practical matter, capacity constraints are not currently a concern for shareholders looking to hold the broad market. For many other strategies, however, capacity is a huge concern, e.g., in high frequency trading.

The limits of compounding

Let’s start with a simple scenario. Suppose you have $1M today and you want to invest it for five years. Suppose only three possible investments are available. First, you can put money in your mattress where it will yield a return of zero. Second, you can buy a five-year CD with an interest rate of 4.9%. Third, you can buy 300 acres of farmland with a purchase price of $1M, which will generate $50,000 of rental income every year and has a resale value of $1M, so it has a yield of 5% and price appreciation of zero.

Which investment is best? Which gets you more after five years? This question seems like a no-brainer. All you do is apply the following equation:

(1)

Plugging in our assumptions, (1) says that after five years, you get $1.27M from the CD but $1.28M from the farmland. Obviously 5% is better than 4.9%, right?

Wrong. (1) is only true when you can reinvest your interim cash flows in the underlying asset, but in this scenario there’s only 300 acres of farmland available and you already own them all. When you receive rental income, you have to do something with this money, and if your only choice is to put it in the mattress, at the end of five years you’ll only have $1.25M. So the best policy is to buy the CD, which beats the other feasible policy of “buy the farmland, put the income in the mattress.”

Equation (1) can be misleading when there are capacity constraints. If you had unlimited ability to buy more acres of farmland every year, then (1) would be fine. But in the presence of capacity constraints, (1) is no longer applicable and you have to tediously track the reinvestment opportunity for each interim payment you receive.

We can’t all reinvest dividends

For an individual shareholder, it’s a great idea to buy a broad market index fund, reinvest the dividends, and hold for one hundred years as seen in Figure 1. The immense increase in your wealth from reinvesting dividends reflects the geometric mean return on U.S. stocks (a.k.a. compound return a.k.a. total shareholder return) in the past century of 10.1% a year, of which 3.7% was dividend yield and 6.4% was price appreciation.

What happens if you had failed to reinvest the dividends and instead used the money for consumption? The dotted line in Figure 1 shows the dire consequences. It shows total price appreciation of the stock market, which measures the wealth you’d have if you’d spent the dividends on beer (instead of reinvesting them). At the end of a hundred years, you’d have drunk a lot of beer, but your wealth would be a measly $500. That’s the incredible power of compounded returns. If you start with $1 and you compound for a century at 10%, that’s a whole different ball game than compounding at 6%. So, yes, reinvesting dividends is a good idea.

But not everyone can hold the market and reinvest dividends. For this reason, Fried, Ma, and Wang (2021) argue that the return to holding stocks is not really 10% for shareholders as a group. Yes, it is 10% for any individual shareholder but not for shareholders as a group. They say:

The stock market generates less wealth than it appears. We show that total shareholder return (TSR), the standard measure of stock investor performance, substantially exaggerates returns earned by these investors in aggregate, and thus by most investors. The main reason: from investors’ collective perspective, dividends cannot be reinvested in public equity, as TSR assumes, but only in other lower-yielding assets … We put forward another measure—“all-shareholder return” (ASR)—which better captures the wealth generated by the stock market for investors. We estimate that the ASR equity premium is 17 to 73% lower than the TSR-implied equity premium, depending on the investment alternative.

The dashed line in Figure 1 shows my version of this idea. Suppose that whenever you receive dividends, you invest them in 1-month T-bills instead of in the stock market. The geometric average return from this policy is 6.8%, as compared to 10.1% from reinvesting in stocks and 6.4% from buying beer.

The policy of investing dividends in T-bills has a time-varying allocation to equities. It starts out in June 1926 with 100% equities, but ends up in June 2025 with 69% equities, 31% T-bills. You could argue that this policy is arbitrary, but that’s kind of the point: you need to do something with dividends, because reinvesting dividends in the stock market is a strategy only open to some shareholders, not all.

We will run out of shares to buy

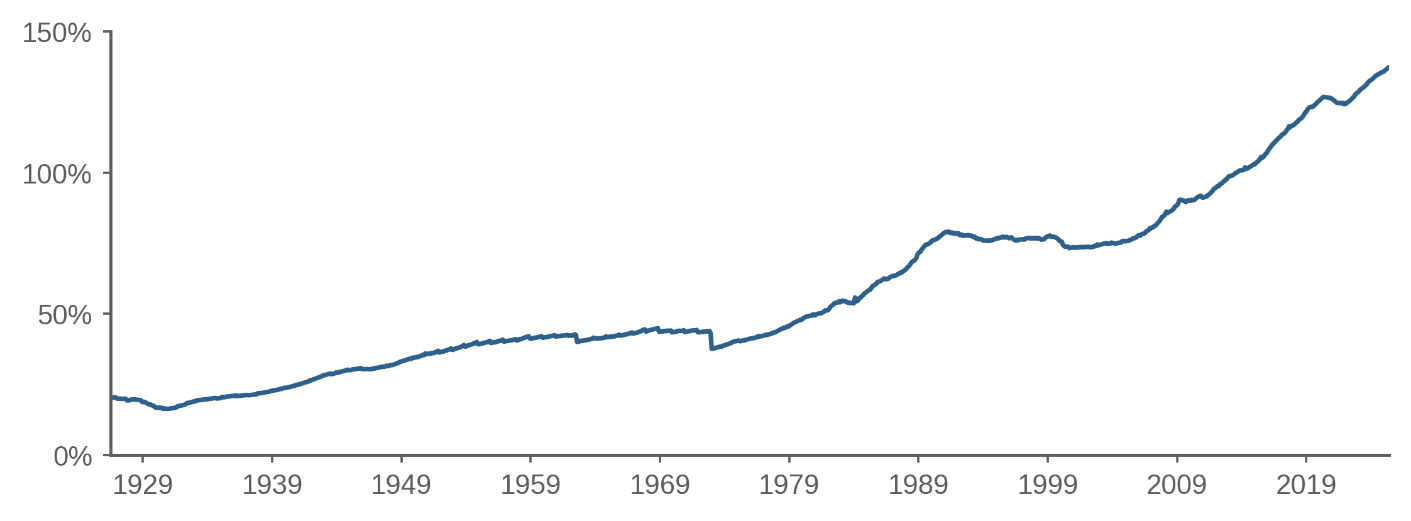

Let’s consider a mindless application of the standard reinvesting dividend strategy shown in Figure 1. Suppose that in June 1926, a hypothetical billionaire named Elon McBezos had purchased 20% of the U.S. stock market and had subsequently reinvested dividends but otherwise had not added or subtracted funds and paid no taxes or other costs. Figure 2 shows the path of his share ownership. This path reflects the ratio between the total wealth shown in Figure 1 (solid line) and the total market capitalization of U.S. stocks.

Figure 2: Fraction of market held by Elon McBezos

Figure 2 shows that an initial purchase of 20% of the stock market in 1926, after reinvesting dividends in the standard manner, would gradually grow as a fraction of the total market. The growing fraction is driven in the first part of the sample mostly by dividend reinvestment (which makes the numerator go up), and in the second half of the sample mostly by repurchasing by firms (which makes the denominator go down).

By 2013, compounded returns imply a portfolio value that is more than 100% of total stock market capitalization, an obviously nonsensical result. Elon McBezos runs out of shares to buy because when you compound at a high return, eventually you end up owning everything. That’s the plot of the 1899 novel The Sleeper Wakes by H.G. Wells: a man falls into a coma and when he wakes up two hundred years later, he owns the entire world due to compound interest. The incredible power of compounding might be a good plot device, but it is a bad description of actual wealth dynamics in the presence of capacity constraints.

Net issuance by firms

In reality, we can never run out of shares to buy because if someone comes to the market seeking to buy, this demand can be accommodated either by higher share prices or more shares being issued by firms. That’s one reason why Figure 2 is nonsensical; in the real world, buying by Elon McBezos would both drive up share prices and induce corporate issuance.

Usually, high share prices and high issuance go together, because firms are smart money. Firms sell when prices are high and repurchase when prices are low. This issuance pattern is another reason (in addition to dividend reinvestment) that the 10% average return on U.S. equities is an overstatement. Yes, 10% is the return on a strategy of reinvesting dividends, but that is not the strategy being pursued by the aggregate shareholder. Instead, the aggregate shareholder must, by the laws of math, be pursuing a strategy of buying when firms are selling and selling when firms are buying.

Dichev (2007) argues that, as a result of issuance:

… investor and security returns differ because of the timing and magnitude of investor capital flows into and out of these securities. The empirical results indicate that actual investor returns are systematically lower than buy-and-hold returns for nearly all major international stock markets. These results imply that the historical equity premium and the cost of equity capital are likely lower than previously thought.

To summarize, although the compound return of 10% per year on U.S. stocks sounds great, that is not what shareholders as a whole are receiving. First, reinvesting dividends implies owning a growing percentage of the stock market and thus is impossible for the aggregate shareholder who owns 100% of all shares. Second, when you own the whole market, you are engaged in a losing timing battle with firms, who will sell you equity when the market is overvalued and buy back equity when it is undervalued. Put these two effects together, and the actual return earned by the aggregate shareholder is closer to 5% than 10%.

What does it mean to “hold the market?”

“Holding the market” is an elusive concept. One challenge is that the market changes over time as firms enter and exit. Lamont (2002) focuses on IPOs and argues that:

The market is often thought of as the epitome of a passive portfolio. But as emphasized by Grossman (1995), the market is actually an actively managed portfolio due to incomplete equitization of assets. When a nontraded firm decides to go public, the composition of the market changes … Although it is not immediately apparent, the dynamic nature of market weights is a pervasive issue in empirical finance.

Pedersen (2018) argues that a “passive” shareholder who holds the market is quite different from an “inactive” shareholder who never trades, and that allegedly passive shareholders must actively trade in order to maintain market cap weights.

But even if we just treat the market as one big firm and ignore its changing composition, “holding the market” could have many meanings. Does it mean you own a growing percentage of all shares (Figure 2) thanks to dividends and repurchases? Does it mean you own a shrinking percentage of all shares, which would happen if you fail to reinvest dividends as in the dotted line in Figure 1? Or does it mean you own a constant percentage of all shares, as is true of the aggregate shareholder who holds 100% of all shares?

Cash distributions by firms make “holding the market” an inherently dynamic strategy. If firms distribute cash as dividends, you need to decide what to do with those dividends. If firms distribute cash as repurchases, you need to decide whether to trade in response.

Capacity vs. compounding

Compounding is the King Kong of wealth creation, but it can be defeated by the Godzilla of limited capacity. Very successful investors, such as Warren Buffett of Berkshire or Jim Simons of Renaissance, eventually run into capacity constraints, and become unable to compound their wealth at high rates of return. Capacity always wins in the end.

According to legend, in 400 A.D. the game of chess was invented by the Brahmin mathematician Sessa, who presented it to the king. The king asked Sessa what reward he wanted for this wonderful invention. Sessa requested that the king reward him with wheat, specifically, one grain of wheat on the first square of the chessboard, two grains of wheat on the second square, and so forth doubling until all 64 squares were covered. The king agreed to this request, not realizing that the power of compound interest implies a total of eighteen quintillion grains of wheat, a sum far exceeding the total world wheat output (either in 400 A.D. or today).

There are two versions of the story’s end. Version 1, Sessa is executed for his impudence. Version 2, the king is grateful for being taught a valuable lesson in the mathematics of exponential growth, and appoints Sessa as his vizier. Based on my experience as a teacher, Version 1 seems more plausible, but either way, the bottom line is that Sessa did not receive the amount of grain that was predicted by compounding due to capacity constraints.

References

Dichev, Ilia D. "What are stock investors' actual historical returns? Evidence from dollar-weighted returns." American Economic Review 97, no. 1 (2007): 386-401.

Fried, Jesse M., Paul Ma, and Charles CY Wang. "Stock investors' returns are exaggerated." European Corporate Governance Institute-Law Working Paper 618 (2021).

Lamont, Owen. "Evaluating value weighting: Corporate events and market timing." (2002).

Pedersen, Lasse Heje. "Sharpening the arithmetic of active management." Financial Analysts Journal 74, no. 1 (2018): 21-36. These materials provided herein may contain material, non-public information within the meaning of the United States Federal Securities Laws with respect to Acadian Asset Management LLC, Acadian Asset Management Inc. and/or their respective subsidiaries and affiliated entities. The recipient of these materials agrees that it will not use any confidential information that may be contained herein to execute or recommend transactions in securities. The recipient further acknowledges that it is aware that United States Federal and State securities laws prohibit any person or entity who has material, non-public information about a publicly-traded company from purchasing or selling securities of such company, or from communicating such information to any other person or entity under circumstances in which it is reasonably foreseeable that such person or entity is likely to sell or purchase such securities. Acadian provides this material as a general overview of the firm, our processes and our investment capabilities. It has been provided for informational purposes only. It does not constitute or form part of any offer to issue or sell, or any solicitation of any offer to subscribe or to purchase, shares, units or other interests in investments that may be referred to herein and must not be construed as investment or financial product advice. Acadian has not considered any reader's financial situation, objective or needs in providing the relevant information. The value of investments may fall as well as rise and you may not get back your original investment. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance or returns. Acadian has taken all reasonable care to ensure that the information contained in this material is accurate at the time of its distribution, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of such information. This material contains privileged and confidential information and is intended only for the recipient/s. Any distribution, reproduction or other use of this presentation by recipients is strictly prohibited. If you are not the intended recipient and this presentation has been sent or passed on to you in error, please contact us immediately. Confidentiality and privilege are not lost by this presentation having been sent or passed on to you in error. Acadian’s quantitative investment process is supported by extensive proprietary computer code. Acadian’s researchers, software developers, and IT teams follow a structured design, development, testing, change control, and review processes during the development of its systems and the implementation within our investment process. These controls and their effectiveness are subject to regular internal reviews, at least annual independent review by our SOC1 auditor. However, despite these extensive controls it is possible that errors may occur in coding and within the investment process, as is the case with any complex software or data-driven model, and no guarantee or warranty can be provided that any quantitative investment model is completely free of errors. Any such errors could have a negative impact on investment results. We have in place control systems and processes which are intended to identify in a timely manner any such errors which would have a material impact on the investment process. Acadian Asset Management LLC has wholly owned affiliates located in London, Singapore, and Sydney. Pursuant to the terms of service level agreements with each affiliate, employees of Acadian Asset Management LLC may provide certain services on behalf of each affiliate and employees of each affiliate may provide certain administrative services, including marketing and client service, on behalf of Acadian Asset Management LLC. Acadian Asset Management LLC is registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration of an investment adviser does not imply any level of skill or training. Acadian Asset Management (Singapore) Pte Ltd, (Registration Number: 199902125D) is licensed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited (ABN 41 114 200 127) is the holder of Australian financial services license number 291872 ("AFSL"). It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Under the terms of its AFSL, Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited is limited to providing the financial services under its license to wholesale clients only. This marketing material is not to be provided to retail clients. Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority ('the FCA') and is a limited liability company incorporated in England and Wales with company number 05644066. Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited will only make this material available to Professional Clients and Eligible Counterparties as defined by the FCA under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive, or to Qualified Investors in Switzerland as defined in the Collective Investment Schemes Act, as applicable.Legal Disclaimer