Bubble Watch, Part 1: Firms are the smart money

Table of contents

Is Nvidia overvalued or undervalued? One way to find out is simply to ask Jensen Huang, the CEO of Nvidia.[1] This method is unlikely to work, however, because corporate executives typically claim that their stock is undervalued, much as parents typically claim their child is above average.[2] A more fruitful approach is to observe Nvidia’s actions. If Huang thinks Nvidia is underpriced, then Nvidia should repurchase equity. If Huang thinks it’s overpriced, or at least less underpriced than usual, then Nvidia should issue equity.

The bad news is that you cannot perfectly infer Huang’s views by observing issuance, because many variables influence issuance. Thus, issuance is not an infallible signal, both because Huang himself is not infallible and because issuance is a noisy measure of his views.

Yet, while not infallible, corporate issuance turns out to be one of the most powerful signals we have for predicting long-term returns. Firms are the smart money, and it pays to imitate them. Thus, when firms are buying their own stock, you should generally buy as well. When firms are selling, you should generally sell as well.

There are hundreds of signals out there, such as momentum, profitability, and value. The optimal systematic strategy should combine them all. But if I were only allowed to use one signal to predict long-horizon stock returns, I’d pick issuance.

Like valuation, issuance predicts returns both at the individual stock level and the aggregate level. For that reason, aggregate issuance is one of my Four Horsemen of the Bubble Apocalypse; when you see a wave of IPOs along with net issuance by existing firms, that’s when you should start worrying about a stock market bubble. In this piece, however, I just want to focus on predicting individual stock returns.

First, I’ll explain what I mean by “smart money,” and give a hypothetical example showing why firms should act as smart money. Next, I’ll explain why issuance reflects causal mechanisms at the heart of economics, and why it is both a symptom of, and a cure for, mispricing. I’ll show how to measure issuance, how it relates to short selling, and why it is arguably the single best predictor of long-term stock returns. Last, I’ll consider whether we are in a 1999-style bubble today.

Dumb money vs. smart money

What is a stock market? It’s a place where different traders come to interact. Let’s categorize these traders into two groups. First, the smart money, who rationally use all available information to make profits from trading. Second, the dumb money, consisting of everyone else. I use the term “dumb money” to describe a diverse group of traders with different motives. They could be literally dumb (as I’ve discussed previously), or they could be trading for fun instead of profit, or they could be index funds, or they could be doing something else entirely.

We can use the framework of smart vs. dumb to understand competing schools of thought in academic finance. Advocates of the efficient market hypothesis don’t deny that dumb money exists, but they think that the smart money always dominates the stock market, and thus prices only reflect forward-looking information about appropriately discounted future cash flows. In contrast, advocates of behavioral finance say that the dumb money sometimes dominates, causing prices to deviate from fundamental value for months or years. Because the dumb money pushes prices away from fundamental value and then prices eventually revert back, the smart money can make profits by buying low and selling high.

The traditional view is that the dumb money is retail investors and the smart money is institutional investors. There’s a lot of truth in that view. As I’ve argued elsewhere, the dumb money definitely includes retail investors. And there are certainly some institutional investors who are smart money, including short sellers and some hedge funds.

So, one view is that the stock market is a chess game being played between retail investors and hedge funds, with retail losing and hedge funds winning (on average). In this view, the firms themselves, such as Nvidia, are just the chess pieces that are being moved around the board by the players.

That view is incomplete. Firms are not chess pieces; they’re chess players, and arguably the best players in the game.

Hypothetical example

If firm management is acting in the interest of long-term shareholders, it should issue overpriced equity and repurchase underpriced equity, when possible.

Here’s a simple example. Imagine that firm XYZ is a holding company and its only assets are 100 carrots, with each carrot worth $1. Suppose XYZ has 100 shares outstanding, its share price is set rationally, and thus each share is worth $1.

Now suppose that a bunch of meme-crazed optimists bid up the price of XYZ to $2 a share. How should XYZ respond?

Suppose XYZ can issue 100 more shares at a price of $2 each, and use the proceeds to buy 200 more carrots. The old shareholders will now own half of a firm with total fundamental value equal to 300 carrots and thus they’ve gained $50. This issuance is a way to transfer $0.50 per share from the crazy optimists to the old shareholders. When market prices eventually return to fundamental value, XYZ will have price $1.50.

In this scenario, XYZ is smart and has locked in a profit of $0.50 per share for the old shareholders by exploiting a temporary window of opportunity in market prices.

Now let’s consider a scenario where XYZ is underpriced. Suppose we start again with 100 carrots and 100 shares, but now the market is excessively gloomy and the share price of XYZ is only $0.50. If XYZ can repurchase 50 shares from the crazy pessimists (financed by selling 25 carrots), $0.50 per share has once again been transferred to each remaining existing shareholder. When the price eventually reverts to fundamental value, the price will again be $1.50.

Are these two scenarios just far-fetched academic thought experiments? No. If you substitute “Bitcoin” for “carrots,” the overpricing scenario describes “Bitcoin treasury firms” as of April 2025, as explained by the indispensable Matt Levine:[3]

The basic situation is that US public equity markets will pay about $2 for $1 worth of Bitcoin. I don’t know why this is, and I am not especially happy about it, but it’s true … Therefore, you should sell Bitcoins on the stock exchange, so people do.

Now, when I think of Michael Saylor, the apostle of Bitcoin treasury, “smart” is not the first word that comes to mind. Nevertheless, I must grudgingly admit that selling something worth $1 for a price of $2 is what the smart money does.

The underpricing scenario is also realistic. For example, in 2022 the Dutch company Prosus owned $134B worth of shares in Tencent, but the market cap of Prosus was below $134B (so substitute “Tencent” for “carrots” and “Prosus” for “XYZ”). Prosus announced a program to repurchase its own shares, funded by selling its Tencent shares. Smart.

Behavioral corporate finance

The idea that corporate equity issuance is driven by perceived mispricing is not new. Lefèvre (1923) wrote:

In every boom companies are formed primarily if not exclusively to take advantage of the public’s appetite for all kinds of stocks.

This idea entered mainstream finance in the 1990s, partly driven by research from Jay Ritter of the University of Florida. Here’s Ritter (1991) explaining why IPOs come in waves and why investing in IPOs is “hazardous to your wealth:”

… (1) investors are periodically overoptimistic about the earnings potential of young growth companies, and (2) firms take advantage of these “windows of opportunity.”

By the 2000s, this idea was part of the new field of “behavioral corporate finance” as described by Baker and Wurgler (2013).

As an empirical matter, firms act like contrarians. When their share price rises, they issue equity. When their share price falls, they repurchase equity. When you ask executives how they make this decision, they say that an important consideration is the “magnitude of equity undervaluation/overvaluation” according to Graham and Harvey (2001).

Not only are firms trying to time the market in their own stock, they are successfully timing the market in their own stock at multi-year horizons. For example, Bradshaw, Richardson, and Sloan (2006) study the stock returns of issuing versus repurchasing firms. They show that firms are smart money: in the years subsequent to issuing/repurchasing, issuers greatly underperform while repurchasers modestly outperform.

Example: GameStop

The movie Dumb Money dramatizes the GameStop episode of 2021, depicting it as an epic struggle of the virtuous retail investors against the evil short sellers (played by Seth Rogen and Nick Offerman). My main complaint about this movie is that it failed to depict the heroic deeds of a key protagonist: GameStop itself.[4]

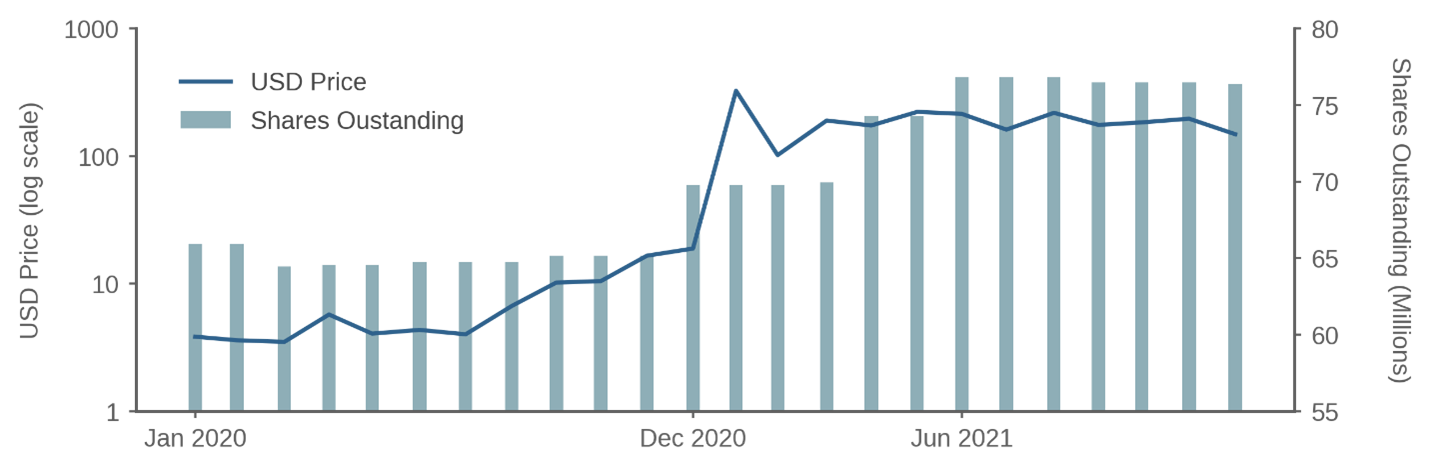

Figure 1: GameStop Price and Shares Outstanding

2020-2021

Figure 1 shows the thrilling action that the movie ignored. We start in mid-2020 where the price of GameStop is around $4 a share. As you can see by the bars, GameStop is repurchasing shares and the number of shares outstanding falls from 66M at the start of 2020 to 65M in mid-2020. Then the share price climbs to almost $19 at the end of 2020; GameStop responds by increasing the number of shares to around 70M. Now the drama heats up, as GameStop’s price soars above $300 in January 2021. GameStop boldly issues more shares in response, ending 2021 with around 76M shares.

Figure 1 shows the classic behavioral corporate finance pattern. GameStop is contrarian, repurchasing when its price is low, issuing when its price is high. And GameStop’s share price subsequent to issuing is consistent with historical patterns; in the period since December 2021, GameStop has greatly underperformed the S&P 500. Conclusion: GameStop is the smart money, selling overpriced shares in 2021 to retail investors.

Supply and demand

Figure 1 shows the free market in action. Price goes up. Supply responds. If people want to buy GameStop shares, then GameStop will create more shares. Supply curves slope upward.

This process was described by Adam Smith in 1776:

If … the quantity brought to market should at any time fall short of the effectual demand … price must rise … The quantity brought thither will soon be sufficient to supply the effectual demand.

Now, you might ask, why didn’t GameStop bring even more shares “thither” in 2021? Why not keep printing shares “sufficient to supply the effectual demand?” The answer is that there are complicated regulatory impediments to issuance, especially in the short term. In some cases, as with AMC in 2021, a company might face a hard limit on the number of shares it can issue.

Let me give two other examples of firms responding to dumb-money demand. First, during the tech-stock bubble, retail investors bought technology mutual funds, and these inflows pushed up the prices of technology stocks. Firms responded by issuing equity. According to Frazzini and Lamont (2008):

Stocks go in and out of favor with individual investors, and firms exploit this sentiment by trading in the opposite direction of individuals, selling stock when individuals want to buy it.… firms respond to $10 billion in flows by issuing $3 billion in stock. Supply accommodates approximately one third of the increase in demand.

Second, Sammon and Shim (2025) look at net buying by index funds, and find a somewhat higher supply response:

when Index Funds demand 1 pp more of a stock’s shares outstanding, Firms take the other side by adjusting the supply of shares by 0.69 pp on average.

The big picture is that issuance is both a symptom of overpricing and a cure for overpricing. Symptom: if you see a firm issuing equity, that’s a good indication that its management believes the firm is overpriced. Cure: If a firm is overpriced, it should eventually find a way to issue enough shares to accommodate the optimists who wish to purchase its shares. Similarly, repurchases (and in the extreme case, going private) are both a symptom of and a cure for underpricing.

The two most important words in economics are supply and demand, and issuance is all about supply. If the price of XYZ is high, XYZ should issue equity, increasing the supply of XYZ shares. Similarly, if the price of tomatoes is high, farmers should grow more tomatoes, increasing the supply of tomatoes. Thus, equity issuance plays a central role in the equity market, just as tomato growing plays a central role in the tomato market.

Issuance as a substitute for short selling

The GameStop episode highlights the limited ability of short sellers to correct overpricing. Short sellers face many constraints, some arising from the dysfunctional nature of the stock loan market. The case of GameStop illustrates another constraint: price risk arising from the actions of the dumb money. You might think that as GameStop’s price went up in January 2021 short sellers would have flocked to sell it. Instead, the opposite happened. Short sellers got killed, they covered their positions, and short interest plunged.

One way to think about issuance is as a substitute for short selling.[5] Both short selling and issuing have the effect of increasing the amount of shares that the optimists can buy; in this way, both the issuers and the short sellers bring supply to the market.

Short sellers create supply using the following mechanism. Suppose there are 66M shares of GameStop, and short sellers borrow 10M shares from existing holders, and sell these shares to new buyers. In this way, the total number of long positions has risen from 66M to 76M. This mechanism stopped working in January 2021 when the short sellers fled. Fortunately, GameStop was there to provide shares to the optimists.

In many ways, GameStop is the natural arbitrageur to correct mispricing of its own shares. Consider what happens to short seller Seth Rogen when prices move against him. If he sells short 10M shares of GameStop at $4 a share, and the price goes to $304 a share, he’s just lost $3B and many unpleasant consequences follow (in the movie, his wife is upset, Nick Offerman is mean to him, and his hedge fund is destroyed). In financial economics, we call this unpleasantness a “limit to arbitrage” that allows the dumb money to run wild.

Now consider, instead, what happens if the CFO of GameStop issues 10M shares when the price is $4, and then the price goes to $304. The CFO may regret this decision, but nobody accuses him of losing $3B.

Thus, issuance by firms is our last line of defense against mispricing. When the barbarians have stormed the gate and the short sellers have fled, firms can continue the battle to restore rational prices.

Information revelation and insider trading

Should we think of issuance as primarily reflecting inside information that only corporate managers have? I don’t think so. While it is true that corporate executives possess private information, information revelation isn’t the main story, because issuance predicts long-term returns.

Why doesn’t the stock market react to the announcement that the firm is issuing or repurchasing? Generally, the market does react in the correct direction, with issuance news sending prices down, and repurchase news sending prices up, as discussed in Ritter (2003). However, prices don’t react enough, and thus returns are predictable at long horizons using past issuance/repurchase decisions.

The academic literature on (legal) insider trading shows the following facts.[6] First, like issuance, insider trading is contrarian. Second, insiders tend to trade in the same direction as the firm, buying around repurchases and selling around issuance. Third, insider trading is independently predictive of future returns. The best time to buy a stock is when both the firm and insiders are buying, and the worst time is when both the firm and insiders are selling.

Measuring net issuance

Issuance seems confusing because firms might be simultaneously repurchasing equity in the open market while issuing equity for executive compensation (as discussed by Mauboussin and Callahan (2024)). Early research separately analyzed different issuance events, such as seasoned equity offerings, repurchase announcements, and stock-financed mergers.

It turns out that there is an extremely simple way to measure firm-level net issuance, a method that gives a holistic view of the net impact of all these different corporate actions. And if you know how to calculate market cap and stock returns, you know how to calculate net issuance.

Here’s the measure: trailing percent change in shares outstanding (split-adjusted, of course) over long horizons such as one to five years. When shares outstanding have risen, that’s bad. When shares outstanding have fallen, that’s good.

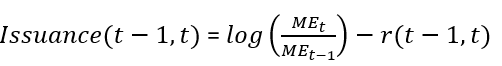

A slight twist on this formula is to treat dividends and repurchases in the same way, so that dividends are a form of negative issuance. That’s the method suggested by Daniel and Titman (2006), who use the following formula for “composite share issuance” between time t-1 and time t:

Here, they calculate issuance as the log percent change in market equity (ME) minus total log returns, where returns include dividends. If instead you use returns ex-dividends, the above formula reduces to just the change in shares outstanding.

GameStop’s increase in shares in 2021 was accomplished by “at-the-market” (ATM) equity offerings. However, historically, ATM offerings have played a minor role. Fama and French (2005) find that stock-financed mergers are the biggest contributor to issuance, with executive compensation in second place, and other methods (seasoned equity offerings, convertible debt, and warrant exercise) are quantitatively less important.

The single best predictor of long-term returns

Many academic studies have documented that net issuance is a powerful predictor of long-term returns.[7] Daniel, Hirshleifer, and Sun (2020) build a model with just two signals, one long-term and one short-term. Their long-term signal is net issuance. They find their parsimonious model predicts stock returns as well as or better than more complicated models that use valuation, profitability, and investment. So for them, issuance is the one best signal for predicting long-term stock returns.

Why is net issuance such a good predictor? Why does it capture the information in other signals, such as value? Here’s Daniel, Hirshleifer, and Sun (2020):

… issuance/repurchase activity is a catchall for many possible sources of “stubborn” investor misperceptions … the strong performance of our financing factor in explaining anomalies suggests that corporate managers are issuing and repurchasing to exploit many of the well-known anomalies.

Firms are the smart money, and no matter how the dumb money manifests itself, the smart money will take the other side. For example, if for some reason profitable firms become overvalued, then profitable firms will issue equity.[8] If instead profitable firms become undervalued, then profitable firms will repurchase equity. Similarly, if internet firms are overvalued (as in 1999) they will issue equity. If quantum firms are overvalued (as today), they will issue equity. In this sense, net issuance is a dynamic signal that reflects mispricing at all times, whether the mispricing involves industries, accounting variables, or whatever.

Where are we today?

Let’s conclude by considering the claim that the U.S. is currently experiencing an AI bubble similar to the tech-stock bubble. I’m skeptical, because today I don’t see a lot of equity issuance by AI-related firms. In contrast, as of 1999, technology firms were issuing equity hand over fist.

Consider the largest five U.S. stocks as of December 1999. All five of them were issuing equity as of December 1999, as measured by the one-year change in the number of shares outstanding. This pattern is consistent with the idea that the whole stock market was overvalued in 1999. Issuance was especially high for leading technology stocks, such as Cisco and Microsoft, suggesting that technology stocks were especially overpriced. Indeed, in September 1999, Steve Ballmer (then President of Microsoft) commented that “there’s such an overvaluation of tech stocks it’s absurd. And I’d put our company’s stock in that category.” As additional evidence, Frazzini and Lamont (2008) show that the top-five firms ranked by largest inflows from retail investors in December 1999 included Cisco and Microsoft.[9] The smart money was selling and the dumb money was buying.

In contrast, among the five largest stocks today, only one is issuing equity (measured by increasing share count as of November 2025) with the other four repurchasing. Today’s environment is just totally different from 1999. The smart money is not selling, at least not yet.

The stock market is a confusing place. We need enduring principles to guide us. Here’s my true north: As long as corporate managers act in the interest of existing shareholders and have the ability to repurchase and issue shares, net equity issuance will predict long-term stock returns. If we are indeed sailing into the stormy seas of an AI bubble, we can rely on issuance to guide us through.

Endnotes

[1] References to this and other companies should not be interpreted as recommendations to buy or sell specific securities. Acadian and/or the author of this post may hold positions in one or more securities associated with these companies.

[2] During the tech stock bubble in 2000, more than 80% of CFOs claimed their stock was undervalued, according to Graham (2022).

[3] “The Stock Market Loves Bitcoin,” Bloomberg, April 24, 2025.

[4] For additional complaints see Lamont, Owen A., and Richard H. Thaler. " ‘Dumb Money’ Exposes the Baffling Allure of Bad Investment Advice." The New York Times (2023): A23-A23.

[5] For more on this point, see Lamont (2004) and Schultz (2023)

[6] See Piotroski and Roulstone (2005), Jenter (2005), Cohen, Malloy, and Pomorski (2012), and Cziraki, Lyandres, and Michaely (2021).

[7] For example, Daniel and Titman (2006), Pontiff and Woodgate (2008), and McLean, Pontiff, and Reilly (2025).

[8] See Greenwood and Hanson (2012).

[9] See Table II of the NBER working paper version of Frazzini and Lamont (2008).

References

Baker, Malcolm, and Jeffrey Wurgler. "Behavioral corporate finance: An updated survey." In Handbook of the Economics of Finance, vol. 2, pp. 357-424. Elsevier, 2013.

Bradshaw, Mark T., Scott A. Richardson, and Richard G. Sloan. "The relation between corporate financing activities, analysts’ forecasts and stock returns." Journal of Accounting and Economics 42, no. 1-2 (2006): 53-85.

Cohen, Lauren, Christopher Malloy, and Lukasz Pomorski. "Decoding inside information." The Journal of Finance 67, no. 3 (2012): 1009-1043.

Cziraki, Peter, Evgeny Lyandres, and Roni Michaely. "What do insiders know? Evidence from insider trading around share repurchases and SEOs." Journal of Corporate Finance 66 (2021): 101544.

Daniel, Kent, David Hirshleifer, and Lin Sun. "Short-and long-horizon behavioral factors." The Review of Financial Studies 33, no. 4 (2020): 1673-1736.

Daniel, Kent, and Sheridan Titman. "Market reactions to tangible and intangible information." The Journal of Finance 61, no. 4 (2006): 1605-1643.

Fama, Eugene F., and Kenneth R. French. "Financing decisions: who issues stock?." Journal of Financial Economics 76, no. 3 (2005): 549-582.

Frazzini, Andrea, and Owen A. Lamont. "Dumb money: Mutual fund flows and the cross-section of stock returns." Journal of Financial Economics 88, no. 2 (2008): 299-322.

Graham, John R. "Presidential address: Corporate finance and reality." The Journal of Finance 77, no. 4 (2022): 1975-2049.

Graham, John R., and Campbell R. Harvey. "The theory and practice of corporate finance: Evidence from the field." Journal of financial economics 60, no. 2-3 (2001): 187-243.

Greenwood, Robin, and Samuel G. Hanson. "Share issuance and factor timing." The Journal of Finance 67, no. 2 (2012): 761-798.

Jenter, Dirk. "Market timing and managerial portfolio decisions." The Journal of Finance 60, no. 4 (2005): 1903-1949.

Lamont, Owen, Short Sale Constraints and Overpricing, in Short selling: strategies, risks and rewards, Frank J. Fabozzi ed., (2004).

Lefèvre, Edwin. Reminiscences of a Stock Operator, New York. 1923.

Mauboussin, Michael J., and Dan Callahan. "Which One Is It? Equity Issuance and Retirement." Counterpoint Global Insights (2024).

McLean, R. David, Jeffrey Pontiff, and Christopher Reilly. "Taking sides on return predictability." Journal of Financial Economics 173 (2025): 104158.

Piotroski, Joseph D., and Darren T. Roulstone. "Do insider trades reflect both contrarian beliefs and superior knowledge about future cash flow realizations?." Journal of Accounting and Economics 39, no. 1 (2005): 55-81.

Pontiff, Jeffrey, and Artemiza Woodgate. "Share issuance and cross‐sectional returns." The Journal of Finance 63, no. 2 (2008): 921-945.

Ritter, Jay R. "The long‐run performance of initial public offerings." The Journal of Finance 46, no. 1 (1991): 3-27.

Ritter, Jay R. "Investment banking and securities issuance." In Handbook of the Economics of Finance, vol. 1, pp. 255-306. Elsevier, 2003.

Sammon, Marco, and John J. Shim. "Who Clears the Market When Passive Investors Trade?." Available at SSRN 4777585 (2025).

Schultz, Paul. "The response to share mispricing by issuing firms and short sellers." Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 58, no. 3 (2023): 1078-1110.

Don't miss the next Acadian Insight

Get our latest thought leadership delivered to your inbox

Legal Disclaimer

These materials provided herein may contain material, non-public information within the meaning of the United States Federal Securities Laws with respect to Acadian Asset Management LLC, Acadian Asset Management Inc. and/or their respective subsidiaries and affiliated entities. The recipient of these materials agrees that it will not use any confidential information that may be contained herein to execute or recommend transactions in securities. The recipient further acknowledges that it is aware that United States Federal and State securities laws prohibit any person or entity who has material, non-public information about a publicly-traded company from purchasing or selling securities of such company, or from communicating such information to any other person or entity under circumstances in which it is reasonably foreseeable that such person or entity is likely to sell or purchase such securities.

Acadian provides this material as a general overview of the firm, our processes and our investment capabilities. It has been provided for informational purposes only. It does not constitute or form part of any offer to issue or sell, or any solicitation of any offer to subscribe or to purchase, shares, units or other interests in investments that may be referred to herein and must not be construed as investment or financial product advice. Acadian has not considered any reader's financial situation, objective or needs in providing the relevant information.

The value of investments may fall as well as rise and you may not get back your original investment. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance or returns. Acadian has taken all reasonable care to ensure that the information contained in this material is accurate at the time of its distribution, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of such information.

This material contains privileged and confidential information and is intended only for the recipient/s. Any distribution, reproduction or other use of this presentation by recipients is strictly prohibited. If you are not the intended recipient and this presentation has been sent or passed on to you in error, please contact us immediately. Confidentiality and privilege are not lost by this presentation having been sent or passed on to you in error.

Acadian’s quantitative investment process is supported by extensive proprietary computer code. Acadian’s researchers, software developers, and IT teams follow a structured design, development, testing, change control, and review processes during the development of its systems and the implementation within our investment process. These controls and their effectiveness are subject to regular internal reviews, at least annual independent review by our SOC1 auditor. However, despite these extensive controls it is possible that errors may occur in coding and within the investment process, as is the case with any complex software or data-driven model, and no guarantee or warranty can be provided that any quantitative investment model is completely free of errors. Any such errors could have a negative impact on investment results. We have in place control systems and processes which are intended to identify in a timely manner any such errors which would have a material impact on the investment process.

Acadian Asset Management LLC has wholly owned affiliates located in London, Singapore, and Sydney. Pursuant to the terms of service level agreements with each affiliate, employees of Acadian Asset Management LLC may provide certain services on behalf of each affiliate and employees of each affiliate may provide certain administrative services, including marketing and client service, on behalf of Acadian Asset Management LLC.

Acadian Asset Management LLC is registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration of an investment adviser does not imply any level of skill or training.

Acadian Asset Management (Singapore) Pte Ltd, (Registration Number: 199902125D) is licensed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited (ABN 41 114 200 127) is the holder of Australian financial services license number 291872 ("AFSL"). It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Under the terms of its AFSL, Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited is limited to providing the financial services under its license to wholesale clients only. This marketing material is not to be provided to retail clients.

Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority ('the FCA') and is a limited liability company incorporated in England and Wales with company number 05644066. Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited will only make this material available to Professional Clients and Eligible Counterparties as defined by the FCA under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive, or to Qualified Investors in Switzerland as defined in the Collective Investment Schemes Act, as applicable.