Bubble Watch, Part 2: A Trillion Reasons We’re Not in an AI Bubble

Table of contents

Is the U.S. stock market currently in an AI bubble? My favorite indicator says no. If corporate executives thought that stock prices were too high, they’d be issuing equity. Instead, they’re repurchasing it, to the tune of $1T in the past year according to Morningstar.[1] That’s a trillion reasons to believe that we’re not in an AI bubble, at least not yet. I call issuance the Third Horseman of the Bubble Apocalypse, and right now, this horseman is nowhere in sight.

Firms are the smart money, and thus high aggregate net issuance would be a symptom that a bubble is occurring. In addition to being a symptom of bubbles, issuance is also a cure for bubbles. Bubbles don’t usually end until an increased supply of shares hits the market, either from existing firms or new firms. In 1999, for example, we saw more than 400 IPOs, and soon the market was overflowing with internet stocks, eventually pushing stock prices downward. But today, we see no similar IPO wave.

Graham (1973) wrote:

… most new issues are sold under “favorable market conditions” – which means favorable for the seller and consequently less favorable for the buyer.

Since we don’t see many new issues, I think today’s market conditions are relatively favorable to the buyer.

Historical bubbles

Let’s take a quick tour through history to see the connection between bubbles and issuance.

In 1720, during the South Sea Bubble, the South Sea Company issued equity in multiple waves of subscriptions. In addition, over 190 “bubble companies” (what we would now call IPOs) were founded in 1720, only four of which subsequently survived according to Chancellor (2000). He quotes the following account published in May 1720:

It is observed that many of these projects are so ridiculous and chimerical, that it is hard to tell which is most to be wondered at, the impudence of those that make the proposals, or the stupid folly of those that subscribe to them …

The British Bicycle Mania of the late 1890s featured a wave of capital flotation and more than 600 new firms created between 1895 and 1897, according to Quinn (2019), who quotes commentary that “cycle shares promise to become as inflated as the tyres.” Few of these new firms survived.

Next, the 1929 U.S. stock market bubble featured enormous issuance by both existing firms and new entrants. Graham and Dodd (1934) blame the underwriters, describing 1929 as:

a wholesale and disastrous relaxation of the standard of safety previously observed by the reputable houses of issue.

The Japan bubble of the late 1980s exhibited a wave of equity issuance that peaked along with equity prices in 1989, according to Goyal and Yamada (2004). Yamada and Takahashi (2015) show that the number of IPOs rose in the 1980s, peaking in 1991.

The U.S. tech-stock bubble had a tsunami of IPOs peaking in 2000. Evidence arising from subsequent legal action against investment banks showed that underwriters privately believed that these new issues were overpriced but nevertheless pushed them on an unsuspecting public.

Measuring aggregate net issuance

Welch and Goyal (2008) provide a simple way to compute the aggregate dollar net issuance for the U.S. stock market in month t:

Net_issuancet = Mcapt - Mcapt-1(1 + Rt)

Mcap is total market cap of all common stock and R is the ex-dividend market return (a.k.a. price return or capital gain return). This formula gives a holistic measure of all the money flowing in and out of the aggregate stock market. A positive number means the supply of shares has gone up; corporations are selling equity to external investors. A negative number means the supply of shares has gone down; corporations are buying from shareholders.

The formula captures all the different forms of issuance by existing firms (including stock offerings and executive compensation) as well as firms entering the market (by IPOs, de-SPACs, and direct listing) and exiting the market (being acquired or going private).[2] For example, Twitter had an IPO in November 2013 (positive issuance) and later went private in October 2022 (negative issuance).

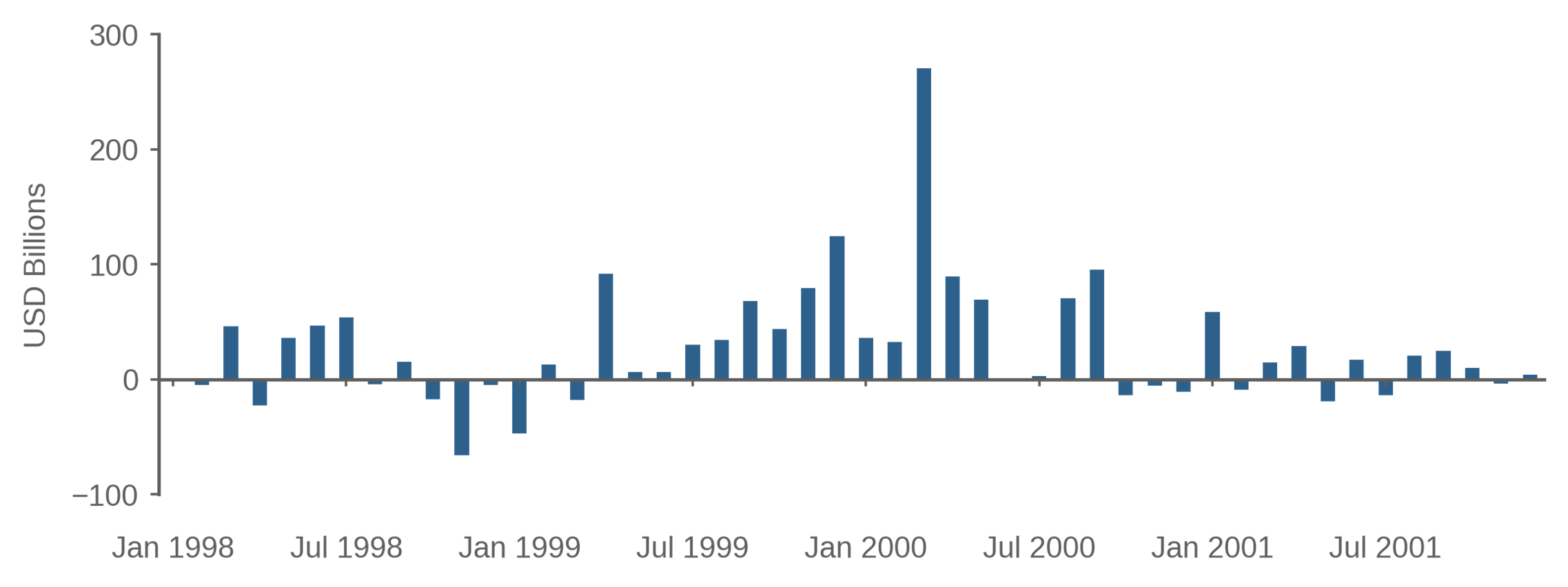

Figure 1 shows aggregate dollar net issuance during the tech-stock bubble. Issuance was mixed in 1998, but turned positive as prices rose in 1999, peaking in March 2000 at more than $250B. Then, as the bubble deflated, issuance turned negative, as firms mostly repurchased equity after mid-2001. So, even if you’d never heard of the tech-stock bubble, you’d be able to detect from Figure 1 that something happened in March 2000.

The formula is based on month-end market values, so it does not literally measure the funds raised by selling equity; instead, it measures the dollar value of shares ultimately entering the market. For example, IPOs are measured by month-end market capitalization, not by IPO proceeds. An alternative way to measure issuance is to carefully track all the shares involved in the IPO, including the initial proceeds and the shares subsequently sold by insiders. That approach, pursued by Ofek and Richardson (2003), shows a similar time pattern with total dollar issuance peaking in February 2000.

Mergers are another important way that firms issue equity, and there were many mergers during this period, as discussed by Lamont and Stein (2006). For example, the merger between AOL and Time Warner, a stock-for-stock transaction announced in 2000, was a fantastic deal for AOL shareholders and was a sign that AOL was overvalued. However, the merger had approximately zero impact on Figure 1, because the dollars flowed from one set of shareholders to another. Thus, while stock-financed mergers are an important signal at the firm level, they are not reflected in the aggregate net issuance.

Another way of thinking about Figure 1 is that it shows that the smart money (firms) was selling in 1999/2000. Therefore, we can infer that the dumb money (retail investors) must have been buying.

Figure 1: Dollar Net Issuance During the Tech-Stock Bubble

January 1998 to December 2002

How do bubbles end?

We can explain the tech-stock bubble using a simple supply and demand story. There were a bunch of optimists who wanted to buy internet stocks in 1999 and 2000. Their demand drove up share prices. In response, existing firms sold shares and various entrepreneurs created new firms that also sold shares. The issuance process was not instantaneous; for example, Pets.com was incorporated in February 1999 and didn’t go public until twelve months later. Eventually, enough shares were issued such that the optimists were satiated, and so share prices fell. That’s the story of Ofek and Richardson (2003), who say:

… to the extent that the magnitude of the volume in new sales pushes the marginal investor away from the optimistic clientele, prices should drop as this huge amount of capital works its way through the market.

Similarly, if the demand for avocado toast surges, the price of avocado toast will rise. It may take months or years for farmers to increase the supply of avocados, during which time the price of avocado toast will remain high. But as supply comes on line, avocado prices will fall.

Thus, part of the reason the tech-stock bubble deflated after March 2000 was the supply of new shares. There were likely other reasons as well: perhaps the optimists changed their minds, perhaps bad fundamental news arrived, or perhaps a “greater fool” mentality kicked in where everyone tried to sell their overpriced shares before it was too late.

If prices were too high in March 2000, why didn’t short sellers step in to profit by selling high? Shouldn’t we see rational speculators correct the mispricing, leaning against the wind and stabilizing prices?

In fact, we saw the opposite. Short interest decreased as the tech-stock bubble inflated. Simply put, short sellers fled the field of battle. Lamont and Stein (2004) find that:

… short-selling does not play a particularly helpful role in stabilizing the overall stock market.

The issuance we observe in 1999/2000 can be understood as a substitute for short selling, as both issuance and short selling are actions that increase the total supply of shares that can be purchased by optimists. However, the risks faced by short sellers and corporate issuers are different. If you shorted Cisco in 1999, you might have lost everything when Cisco’s price subsequently doubled.[3] That’s the relentless savagery of mark-to-market accounting. But when Cisco’s managers decided to issue shares in 1999 and subsequently Cisco’s price doubled, the managers did not suffer adverse consequences. As Lamont and Stein (2004) say:

A nonfinancial manager who issues equity … does so in the closed-end corporate form, and without being subject to mark-to-market accounting. Thus, if the market continues to go up, she will not record a loss, and she will certainly not be faced with the threat of liquidation.

Bubbles do not end due to the actions of short sellers or contrarians, most of whom are long gone by the time the bubble reaches its peak. They end, at least in part, due to issuance.

A century of issuance

To put net issuance into meaningful units, define scaled issuance as the trailing 12-month sum of net issuance, divided by the total capitalization of the market today.[4] If this number is +5%, for example, it means that 5% of the current market consists of shares that were issued in the past year.

Figure 2: 12-month Net Issuance as Percent of Market Cap

February 1927 to September 2025

Figure 2 shows scaled issuance over the past century.[5] We mostly see positive issuance prior to the 1980s when repurchasing became common. We see negative issuance in times of extremely low stock prices, such as 1932, when firms go private and exit the stock market.

We see significant repurchases following the stock market crash of 1987 and then many years of positive issuance in the 1990s. In the past 20 years, we mostly see repurchases, with scaled issuance averaging -1% since 2005, as profitable firms distributed cash to shareholders.

You can see the two major U.S. stock market bubbles of the past century, 1929 and 2000, reflected in scaled issuance in Figure 2. I’d argue that we had a smaller bubble peaking in 2021, which is also apparent in Figure 2.

The method used in Figure 2 is not the only way to measure issuance.[6] But various different methods generally produce results similar to Figure 2. Firms are contrarian. They issue when prices are high and repurchase when prices are low.

Are we in an AI bubble today?

The latest observation in Figure 2 is September 2025 and shows scaled issuance of -0.9%. That’s approximately the average level over the period 2005 to 2025. U.S. corporations are repurchasing equity today, just as they’ve generally been doing for the past 20 years.

Another way to describe today’s market is to say that equity owners are getting a dividend yield of 1.2%, plus another 0.9% of cash distribution via net repurchases, for a total net cash distribution yield of 2.1%. During the tech-stock bubble, the U.S. stock market was a cash furnace, a money pit into which credulous investors shoveled their wealth. In contrast, today’s market is a disciplined cash-generating machine that is diligently rewarding shareholders with distributions.

Based on Figure 2, we’re not currently in an AI bubble, because we don’t see a wave of net issuance. We know that it’s possible for us to have a wave of issuance, since we had one only four years ago. But it’s just not here.

Can there be a bubble with no issuance? Yes, in an asset class such as Bitcoin where discretionary issuance is impossible. Indeed, the genius of Bitcoin is that it’s hardwired to be bubble prone. In some equity markets, such as mainland China, issuance is a regulated activity and thus behaves differently. In markets where equity issuance is possible, however, I’m unaware of any historical example of outrageously high equity prices that are not accompanied by a wave of issuance.

We currently see many signs of speculative excess in the U.S. stock market. But for me, issuance is the most reliable bubble indicator because it’s easy to measure, has a strong theoretical foundation, and an impressive historical track record. Thus, I doubt that the U.S. stock market is in a bubble as of November 2025.

How fast could we transition from our current condition into bubble mode? Pretty fast. In March 1999, for example, scaled issuance was slightly negative. A year later, in March 2000, scaled issuance flipped to 5%. Maybe that will happen again. But so far, nothing.

Endnotes

[1] “Stock Buybacks Are Booming in 2025. That’s Bad News for Dividend Investors,” Morningstar, October 8, 2025. The $1T is gross repurchases, but as discussed later, if you subtract gross issuance, you get net repurchases over the trailing year through September 2025.

[2] I use CRSP data for common stock and thus I exclude ADRs, closed-end funds, REITs, and SPACs. When a SPAC de-SPACs, it becomes a common stock, which I count as issuance.

[3] References to this and other companies should not be interpreted as recommendations to buy or sell specific securities. Acadian and/or the author of this post may hold positions in one or more securities associated with these companies.

[4] An alternative definition of net issuance treats dividends as interchangeable with repurchases, and uses total returns (instead of ex-dividend returns) in the equation. The resulting scaled issuance is the negative of “net total shareholder yield” as defined by Mauboussin and Callahan (2025). See also my prior discussion of shareholder returns and Boudoukh, Michaely, Richardson, and Roberts (2007).

[5] Details: I set net issuance equal to zero in August 1962 (when CRSP added coverage for stocks from the American Stock Exchange) and January 1973 (when CRSP added NASDAQ).

[6] See Baker and Wurgler (2000), Lamont (2002), and Greenwood, Shleifer, and You (2019).

References

Baker, Malcolm, and Jeffrey Wurgler. "The equity share in new issues and aggregate stock returns." the Journal of Finance 55, no. 5 (2000): 2219-2257.

Boudoukh, Jacob, Roni Michaely, Matthew Richardson, and Michael R. Roberts. "On the importance of measuring payout yield: Implications for empirical asset pricing." The Journal of Finance 62, no. 2 (2007): 877-915.

Chancellor, Edward. Devil take the hindmost: A history of financial speculation. Penguin, 2000.

Goyal, Vidhan K., and Takeshi Yamada. "Asset price shocks, financial constraints, and investment: Evidence from Japan." The Journal of Business 77, no. 1 (2004): 175-199.

Graham, Benjamin. The Intelligent Investor, 1973.

Graham, Benjamin, and David L. Dodd. Security analysis: principles and technique. 1934.

Greenwood, Robin, Andrei Shleifer, and Yang You. "Bubbles for Fama." Journal of Financial Economics 131.1 (2019): 20-43.

Lamont, Owen A., and Jeremy C. Stein. "Aggregate short interest and market valuations." American Economic Review 94, no. 2 (2004): 29-32.

Lamont, Owen A., and Jeremy C. Stein. "Investor sentiment and corporate finance: Micro and macro." American Economic Review 96, no. 2 (2006): 147-151.

Lamont, Owen. "Evaluating value weighting: Corporate events and market timing." NBER Working Paper 9049, 2002.

Mauboussin, Michael J., and Dan Callahan. "Capital allocation." Counterpoint Global Insights (2025).

Ofek, Eli, and Matthew Richardson. "Dotcom mania: The rise and fall of internet stock prices." The Journal of Finance 58.3 (2003): 1113-1137.

Quinn, William. "Technological revolutions and speculative finance: evidence from the British Bicycle Mania." Cambridge Journal of Economics 43, no. 2 (2019): 271-294.

Welch, Ivo, and Amit Goyal. "A comprehensive look at the empirical performance of equity premium prediction." The Review of Financial Studies 21, no. 4 (2008): 1455-1508.

Yamada, Kazuo, and Hidenori Takahashi. "IPOs, Growth, and the Impact of Relaxing Listing Requirements." Available at SSRN 2200771 (2015).

Legal Disclaimer

These materials provided herein may contain material, non-public information within the meaning of the United States Federal Securities Laws with respect to Acadian Asset Management LLC, Acadian Asset Management Inc. and/or their respective subsidiaries and affiliated entities. The recipient of these materials agrees that it will not use any confidential information that may be contained herein to execute or recommend transactions in securities. The recipient further acknowledges that it is aware that United States Federal and State securities laws prohibit any person or entity who has material, non-public information about a publicly-traded company from purchasing or selling securities of such company, or from communicating such information to any other person or entity under circumstances in which it is reasonably foreseeable that such person or entity is likely to sell or purchase such securities.

Acadian provides this material as a general overview of the firm, our processes and our investment capabilities. It has been provided for informational purposes only. It does not constitute or form part of any offer to issue or sell, or any solicitation of any offer to subscribe or to purchase, shares, units or other interests in investments that may be referred to herein and must not be construed as investment or financial product advice. Acadian has not considered any reader's financial situation, objective or needs in providing the relevant information.

The value of investments may fall as well as rise and you may not get back your original investment. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to future performance or returns. Acadian has taken all reasonable care to ensure that the information contained in this material is accurate at the time of its distribution, no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to the accuracy, reliability or completeness of such information.

This material contains privileged and confidential information and is intended only for the recipient/s. Any distribution, reproduction or other use of this presentation by recipients is strictly prohibited. If you are not the intended recipient and this presentation has been sent or passed on to you in error, please contact us immediately. Confidentiality and privilege are not lost by this presentation having been sent or passed on to you in error.

Acadian’s quantitative investment process is supported by extensive proprietary computer code. Acadian’s researchers, software developers, and IT teams follow a structured design, development, testing, change control, and review processes during the development of its systems and the implementation within our investment process. These controls and their effectiveness are subject to regular internal reviews, at least annual independent review by our SOC1 auditor. However, despite these extensive controls it is possible that errors may occur in coding and within the investment process, as is the case with any complex software or data-driven model, and no guarantee or warranty can be provided that any quantitative investment model is completely free of errors. Any such errors could have a negative impact on investment results. We have in place control systems and processes which are intended to identify in a timely manner any such errors which would have a material impact on the investment process.

Acadian Asset Management LLC has wholly owned affiliates located in London, Singapore, and Sydney. Pursuant to the terms of service level agreements with each affiliate, employees of Acadian Asset Management LLC may provide certain services on behalf of each affiliate and employees of each affiliate may provide certain administrative services, including marketing and client service, on behalf of Acadian Asset Management LLC.

Acadian Asset Management LLC is registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Registration of an investment adviser does not imply any level of skill or training.

Acadian Asset Management (Singapore) Pte Ltd, (Registration Number: 199902125D) is licensed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited (ABN 41 114 200 127) is the holder of Australian financial services license number 291872 ("AFSL"). It is also registered as an investment adviser with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Under the terms of its AFSL, Acadian Asset Management (Australia) Limited is limited to providing the financial services under its license to wholesale clients only. This marketing material is not to be provided to retail clients.

Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority ('the FCA') and is a limited liability company incorporated in England and Wales with company number 05644066. Acadian Asset Management (UK) Limited will only make this material available to Professional Clients and Eligible Counterparties as defined by the FCA under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive, or to Qualified Investors in Switzerland as defined in the Collective Investment Schemes Act, as applicable.